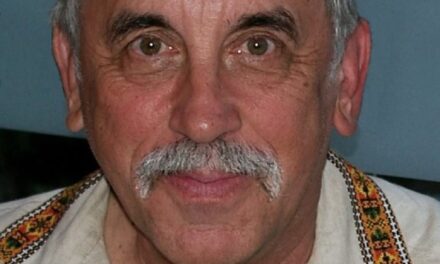

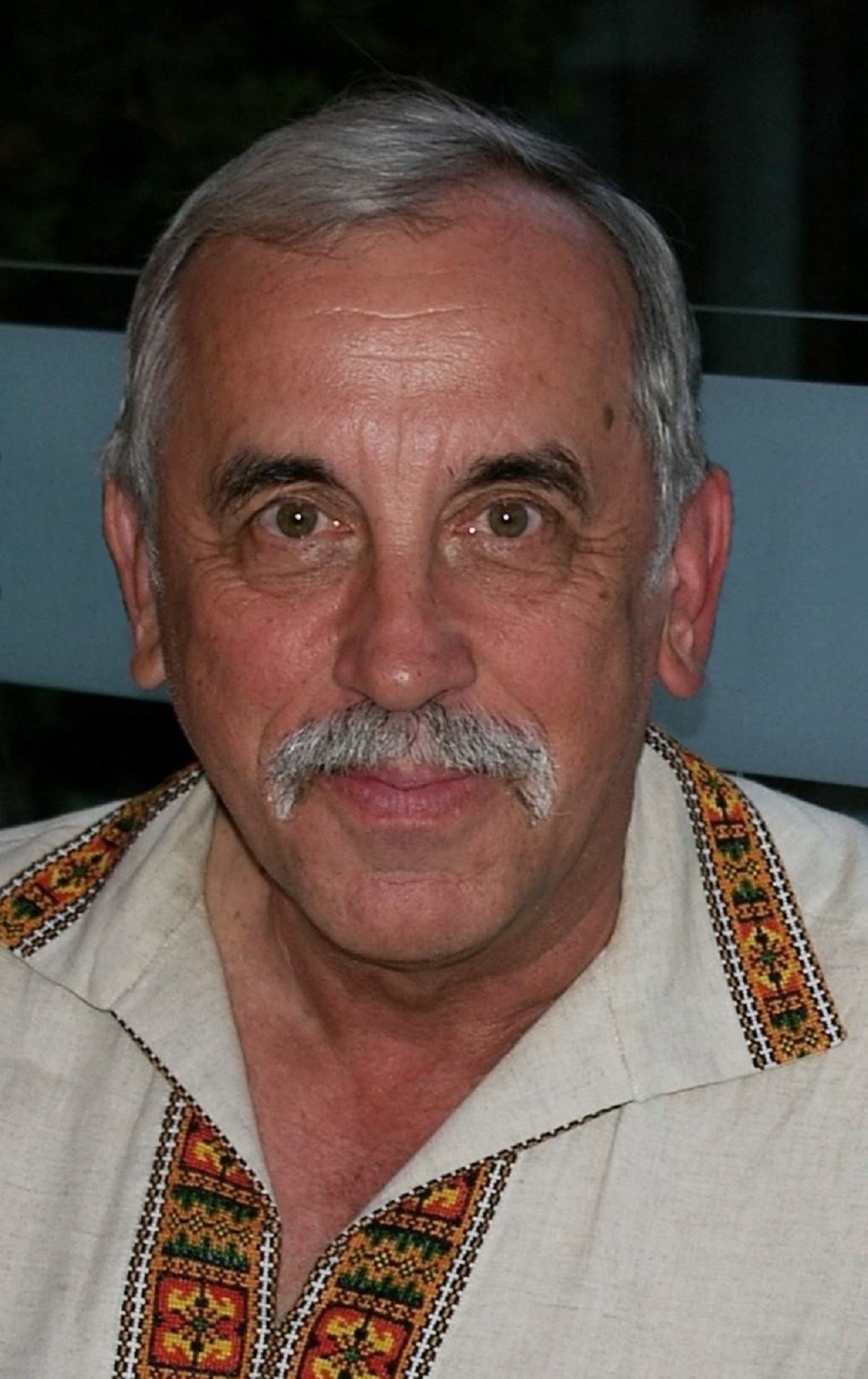

Mariya Chubata for NP-UN.

“Good universities are built around a good idea” – Stefan Behnisch

Stefan Behnisch, together with his partners from the firm Behnisch Architekten, has designed dozens of buildings during his successful career. His most recent project, the Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Centre at the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv, Ukraine, will open September 10, 2017. In terms of design and concept, the Centre is a unique structure in Ukraine which has generated great excitement in advance of the grand opening and consecration of the new Centre. We met with architect Stefan Behnisch and spoke with him about the project, and the specific challenges he faced designing the Centre.

Mr. Behnisch, I would like to begin with a question about your decision to become an architect. As a student in Munich, you first studied philosophy and economics and only later studied architecture at the Technical University of Karlsruhe. Why did you change the initial track you were pursuing and choose to pursue architecture instead?

Thank you for that question. Architecture had always been an important part of my life. My father was a well-known architect in Germany. He was an architect for the Olympic facilities in Munich, for example. When I finished school, everybody expected me to become an architect. Therefore, initially, I decided not to become an architect. I wanted to be a journalist. So what education does one need to be a good journalist? You try to find a field in which to be an expert. The most general field of study I found was philosophy. At the same time, I began my studies in macroeconomics – the political side of economics. That direction was more interesting for me than microeconomics.

However, in reality, I was not free from architecture. I deeply understood the principles and purpose of architecture, good design. During my childhood, all our family vacations were about visiting interesting places, discussing buildings. As a result, I had already started my education in architecture from basics.

What were the main influences that shaped your design principles and philosophy?

I think it is rather a mix of different experiences. Past experiences shape us, how we think, how we make decisions.

I had always shared the humanistic ideals of my father. Also, studying philosophy influenced a certain way of thinking – to design a building with respect for our environment, nature, for society, for people as a whole, as well as individuals in particular. You understand that architecture is not for the architect, but for the people who will use the building. Fundamentally, my design philosophy is about respect.

And while I have people whom I consider to be my architectural heroes, I always tell my students this: if you have a hero, please make sure that he or she has been dead for at least for 50 years. Do not declare a living person to be your hero, at least not publicly. Otherwise, you will constantly be compared and always be seen and perceived as a reflection of that person.

Can you describe the evolution of your work?

Of course, when you begin a career, you are more naïve, maybe more idealistic, than when you are 60. This does not mean better or worse – just means different. I think the most important idea for me in terms of career and development is to really understand and resist the temptation to think that you know it all. I genuinely believe that the more you learn, the more you understand how much you still do not know.

I consider that the most important aspect of learning is that it opens a gate for more knowledge. Learning is like an iceberg – you see only the top of it. We may grow wiser and more knowledgeable, but the crucial part is to understand that you will never and can never know everything. Therefore, you must remain open.

I have found that with age I have become more inquisitive. If you must work simply to feed yourself and your family, then there is not much room for curiosity. My team and I are in a privileged situation where we can afford to be and remain inquisitive. I have an idea to open a new office in Berlin that will do only research.

Which of your projects were the most special for you?

There are key projects that have opened new horizons for us. One of them was a pilot project in sustainable architecture in the early 1990s. This opened a new world for us. Then there was the Genzyme Center in Cambridge, our first project in America. However, some of the most interesting projects were never built. They were well researched and fantastic, but never reached the pragmatic phase of realization.

The Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Centre of UCU visually reminds us of a stack of books. What is behind this design concept?

Architecturally, it was interesting for us to rethink the role of a library in the university of the 21st century. A traditional understanding of library defines it as a big storage area for books, where students could go and read, do research, most often, individually. With the development of electronic media and technologies for more and more universities, libraries become broader centers for learning and communication. The library of the new age is a place where people work and study together. The library is less about the pure storage of books, it is more about a place of communication. However, books continue to symbolize knowledge, the essence of a library.

There are many mistakes made during the last 30 years from which we should learn. Many libraries have not really functioned well because they continued to follow an outdated concept. In this design, we wanted to get it right. Our goal was to create a building that is flexible enough to adjust over time to the different needs of the university, students, and faculty. Architecturally, that had some implications – the ground floor is very public, allowing the community to gather. The other floors are designed for study, and there is a more restrained administrative floor on top. We decided to create the facade that makes a distinction between the need for light, and the need for visual contact with the outdoors. You can almost sit in the window to read, to be part of landscape outside, and from the outside, see what is happening in the library. On the exterior, a part of the university church is reflected on the façade, as well as the green park and blue sky. The building will be a good neighbor. The building will have its own identity, but will also absorb its surroundings.

This is your first project in Ukraine, with a Ukrainian partner. How was this experience?

I find that it is always rewarding to work with intelligent people and in a university you meet the most intelligent people. I did not come with specific expectations. I understand that this is Central Europe, which has a different history than Western Europe, and I know there is a German-Ukrainian past, which, to be honest, is a very difficult one. There is the new Ukrainian-Russian experience that influences society greatly.

Continued in the next issue.

Share on Social Media