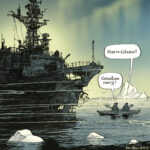

Editorial cartoon by David Parkins, Globe and Mail

Marco Levytsky, Editorial Writer.

April 4 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Defence Minister Bill Blair released a defence policy update entitled “Our North, Strong and Free,” which claims to be ““a significant step forward in our efforts to reach the NATO commitment of 2% to which we agreed at the Vilnius Summit in 2023”.

That’s a hollow claim.

The plan calls for an investment of $8.1 billion over the next five years, which is expected to increase the spending-to-GDP ratio from 1.38% to 1.76% by 2029-30. The document does not include a yearly breakdown of how Canada’s spending will grow by that amount, but much of the detailed spending is back-ended and falls after the 2025 federal election. Even if Canada reaches its defence spending targets by the end of the decade, it would still be “$6 billion to $7 billion” short of NATO’s two per cent of GDP benchmark for member nations, says Defence Minister Bill Blair.

Neither is there a target date for Canada to hit the actual 2% mark. Instead, it calls for $73 billion to be invested over the 20 years after 2030. What $73 billion will be worth in 2050 is anybody’s guess. Even if it does reach 2% in 25 years, what will the world look like then?

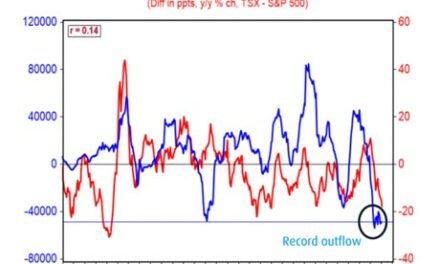

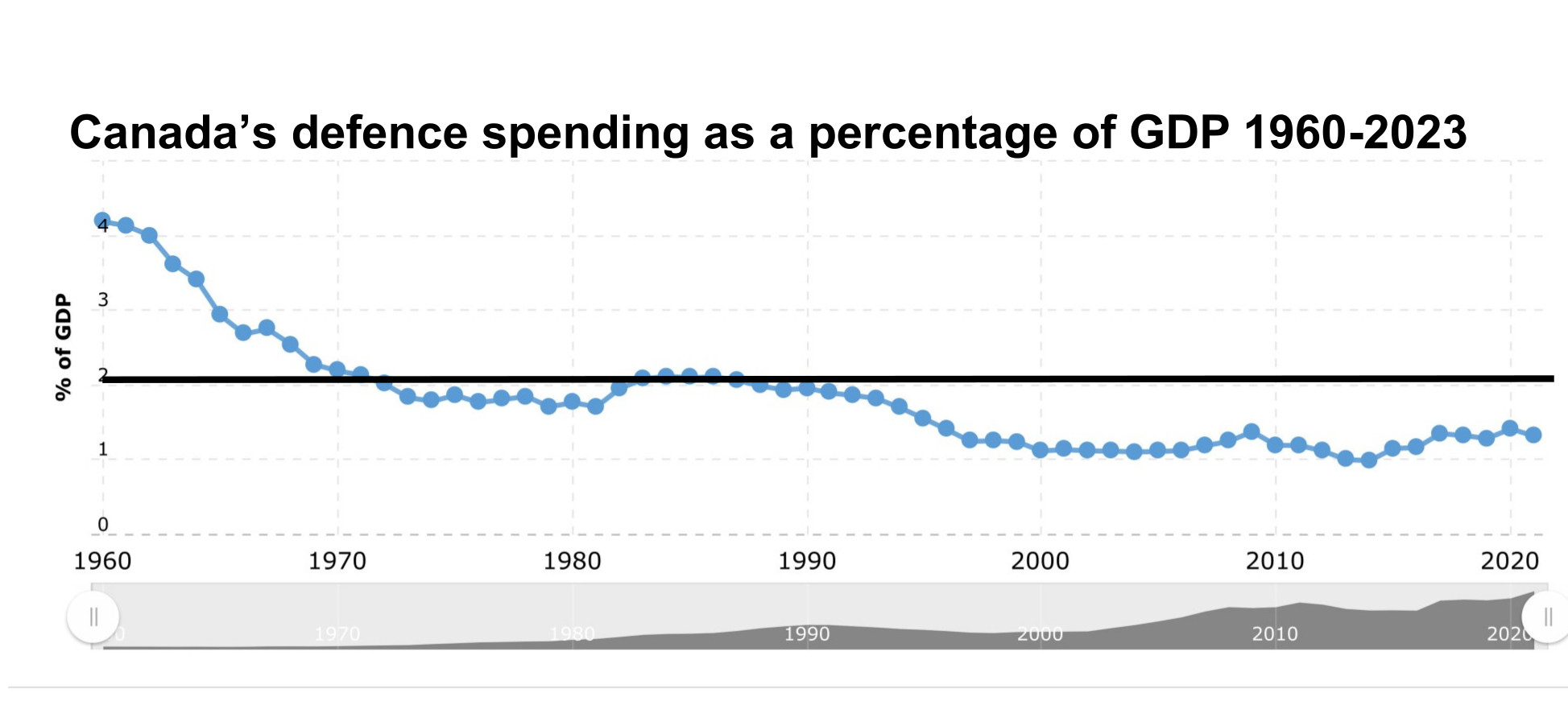

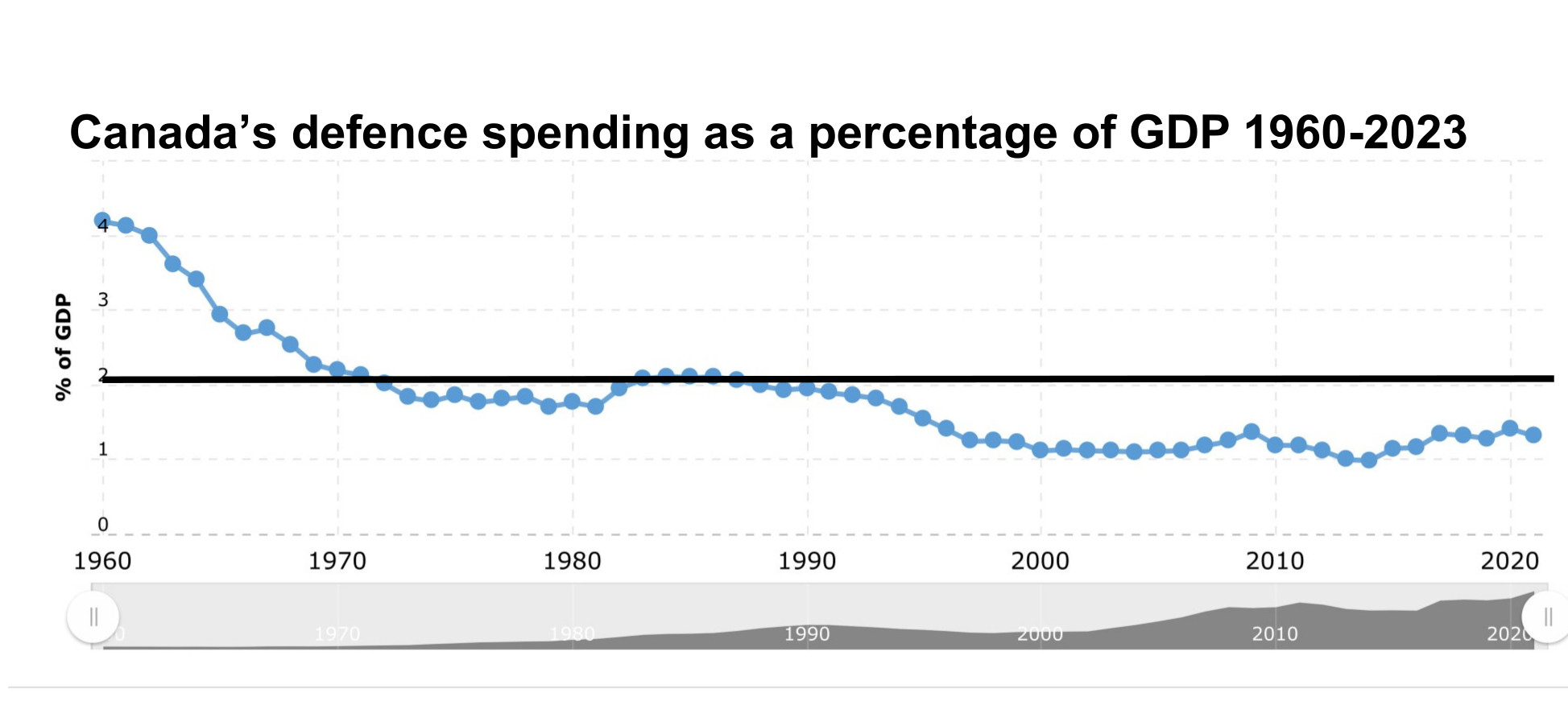

Canada’s defence spending has exceeded the 2% of GDP ratio in the past and can do it again if the political will exists. In 1960, at the height of the Cold War, it reached 4.19%. As tensions eased after the Cuban Missile Crisis the ratio declined but hovered in that general area until the late 1980s (See graph). It dipped to 1.82% by the end of the Mulroney administration in 1993. Then, under Prime Minister Jean Chretien and his Finance Minister Paul Martin, the real nosedive began. As finance minister, Martin made huge budget cuts and produced a balanced budget in 1998, which occurred only twice in 36 years before 1997.

But there was a cost – especially where defence spending was concerned. By 1997 it had fallen to 1.25% of GDP and by the end of Chretien’s administration in 2003 to 1.12% where it remained throughout Martin’s three-year tenure as Prime Minister.

Defence spending was an easy target. It was less politically damaging than cuts to other government services, and there had always been a tendency to downplay the need for more defence spending since we could always ride on the backs of the United States, knowing well that the Americans would never allow a hostile takeover of its vast northern border. Basically, we were freeloading.

Also, during the nineties, there was a naïve belief that the world was a much safer place due to the dissolution of the USSR and what was generally assumed to be the end of the Cold War. The apex of this naivety was the 1992 publication of “The End of History and the Last Man” by American political scientist Francis Fukuyama who argued that with the ascendancy of Western liberal democracy – following the demise of the Soviet Union — humanity has reached “not just … the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: That is, the end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” (Incidentally, Fukuyama today recognizes Russia’s danger and was among the more than 35 artists, activists, scholars and others who, on April 10, called upon Congress to provide enough funding for Ukraine to win the war.)

But whatever optimism may have been prevalent during the nineties, all that changed with the election of Vladimir Putin as President of Russia. He pulled the wool over the eyes of Western leaders early in his tenure. Yet the evidence of his aggressive inclinations was there right from the beginning. Perhaps the murder of journalists and the massive carnage he inflicted upon Chechnya during the Second Chechen War could be dismissed as internal matters. Still, certainly, the 2008 invasion of Georgia, the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the subsequent invasion of Ukraine’s Donbas demonstrated his total disregard for the sovereignty of his neighbouring foreign states and his threat to world peace.

Nevertheless, Canada’s neglect of its defence sector continued. There was virtually no change in the spending-to-GDP ratio during the Harper years. It was 1.13% in 2006 and increased to 1.15% in 2013. Under Trudeau it climbed to 1.21% in 2020 but fell again the following year.

The incremental increases that the government proposes may have been appropriate 20 years ago, but they are woefully inadequate today. When a house is burning, you need full blasts of water to put it out – not a series of dribs and drabs that will allow the fire to spread even further.

But that is what is happening today. Ukraine is on fire, and if the rest of the democratic world does not provide enough to put that fire out, it will spread even further and engulf the rest of Europe. That means NATO members and Canada as a NATO member will be obligated to defend them.

While the current situation is fraught with danger, it could get much worse, especially should Donald Trump, who has promoted neo-isolationism and questioned the need for collective security, be re-elected President of the United States. He has also pledged to stop sending aid to Ukraine, which will put pressure on other countries, including Canada, to increase their contributions massively unless they want to let Putin take over Ukraine and then advance upon the rest of Europe.

NATO is an alliance built upon collective security. To maintain that security, each member must contribute their fair share, which is 2% of GDP.

Canada has been riding on the back of the United States for too long. As a result of our meagre defence spending, we have allowed our equipment to deteriorate seriously. Witness the recent debate over the supply of CRV7 rockets to Ukraine. Why can’t we send them to Ukraine? Because they have been degraded to such an extent that they may become dangerous to those who fire them. Regarding the neglect of our defence sector, both Liberal and Conservative governments are to blame. And while Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre criticizes the current Liberal plan, he has not come up with a deadline to reach the 2% requirement either.

It is time for all Canadian parties to wake up to the real danger facing today’s world. This is not the time for piecemeal measures. It’s a time for resolute action. We must proceed towards reaching our NATO obligations at full speed. Failure to do so will make us an undependable partner and lead to disastrous consequences.

Share on Social Media