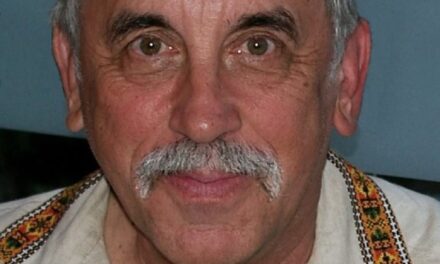

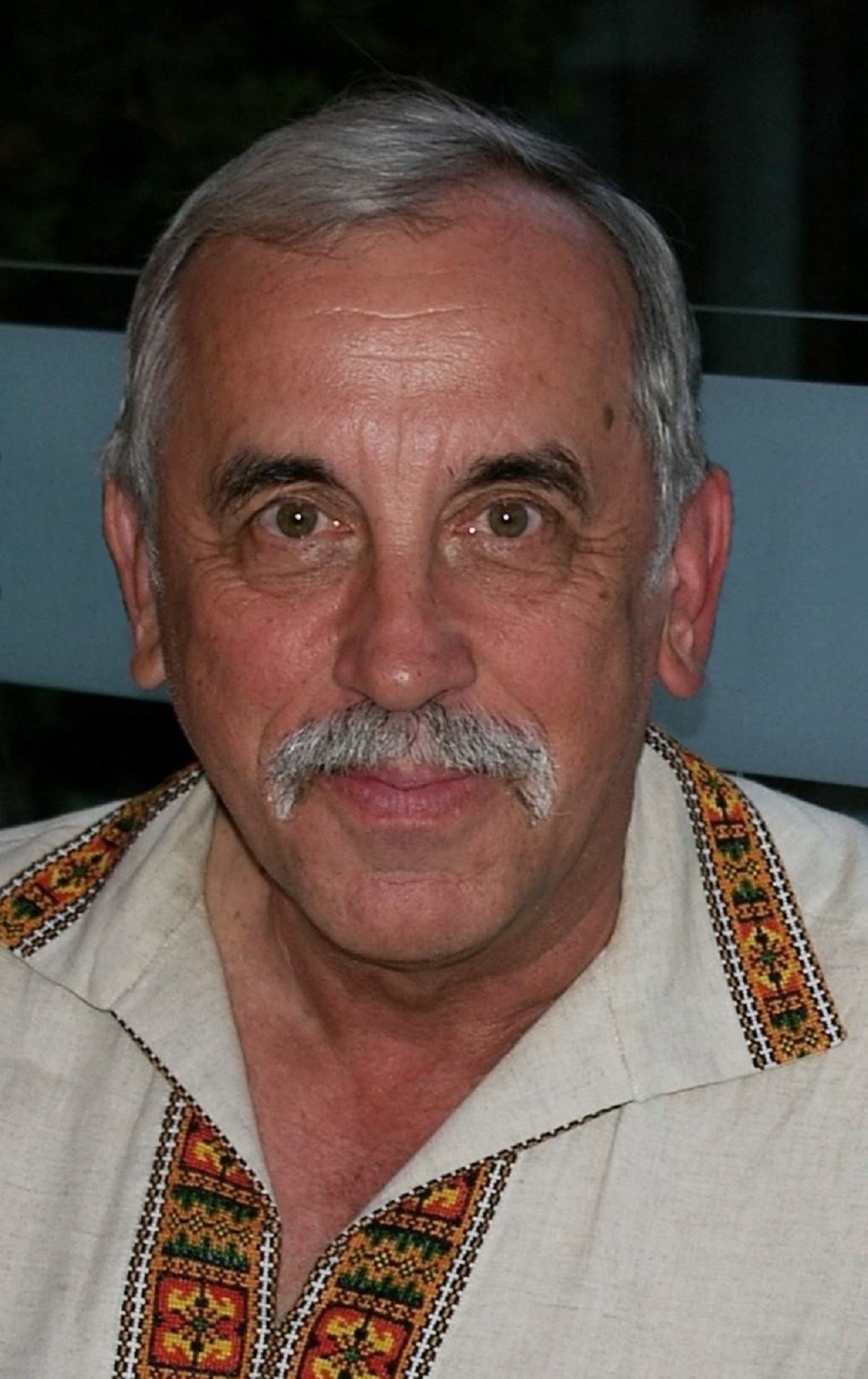

Olena Goncharova for New Pathway – Ukrainian News.

In 2019 the Ukrainian Orthodox Church broke away from Russia, 27 years after Ukraine became independent from the Soviet Union. But this was not a 27-year battle, according to Nicholas Denysenko, a deacon of the Orthodox Church in America who serves as Emil and Elfriede Jochum Professor and Chair at Valparaiso University.

On March 12, Dr. Denysenko explained Ukrainian autocephaly as well as politics, history, and ecclesiology in his presentation during the Bohdan Bociurkiw Memorial Lecture at St. John's Cultural Centre in Edmonton.

Dr. Denysenko previously taught at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. He is a graduate of the University of Minnesota, St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary, and The Catholic University of America, where he received his Ph.D. in 2008. His most recent books are The People's Faith: The Liturgy of the Faithful in Orthodoxy (2018), and The Orthodox Church in Ukraine: A Century of Separation (2018).

NP-UN shares the highlights of the lecture.

In 2018-2019, Ukraine's Orthodox Church (OCU) became a featured story in the mainstream media. “The drama peaked with a Council in December 2018 that attempted to unify the divided orthodox churches in Ukraine and was completed when the newly elected Metropolitan Epiphanius received a Tomos of autocephaly (which codifies a decision by a holy synod, or council of Orthodox bishops) from Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew on January 6, 2019,” said Dr. Denysenko.

The role of the independent Ukrainian church is more than just spiritual. A separate church for Ukraine goes against the Russian imperial concept of the historic and spiritual unity of Ukrainians and Russians. It contradicts the belief that these nations are part of one country.

However, it was not Ukraine's first attempt to receive autocephaly, or independence, to its Orthodox Church.

Earlier attempts

Back in 1686, Ecumenical Patriarch Dionysius IV gave legal authority over the Kyiv Orthodox church to Moscow under pressure from the Russian tsar. “Moscow had interpreted this decision as a complete transfer of church jurisdiction,” Dr. Denysenko explained. This move provoked protests by Ukrainian clergy and parishioners. Many Ukraine's religious scholars compare it to church annexation.

About 100 years ago, following the break-up of the Russian Empire, Ukrainians made their first big attempt to end their church's subordination to Russia.

However, the “instability of Ukrainian politics” prevents any one of the church parties from establishing strong roots in Ukraine, according to Dr. Denysenko.

In January 1919, the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic, a short-lived state that existed in 1917–1921, passed a law on the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. The government also sent its envoy to Istanbul to ask the Ecumenical Patriarch to recognize the Ukrainian church.

But that never happened. None of the Orthodox bishops supported church independence. So, in October 1921, priests and parishioners consecrated Vasyl Lypkivsky as their metropolitan without bishops and in violation of Orthodox norms.

This new church was popular among the people. But after the Soviet Union took control of Ukraine, it suppressed the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church. Most of its priests were imprisoned or killed during the Great Terror of 1930–1937.

The second attempt to form an independent Ukrainian church came in the 1940s, during World War 2. The Polish Orthodox Church, which largely consisted of Ukrainians living on the territory of Poland, started consecrating bishops for Ukraine. In this way, the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church was established as a part of the Polish church. It spread to the rest of Ukraine, which was occupied by Nazis at the time.

In 1942, Nazi authorities recognized the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church. But soon after, they stopped supporting the church because it had close ties to Ukrainian nationalists. When the Soviets regained control over Ukraine in 1944, this church was banned. Some of its bishops emigrated to Canada and the United States.

“The stability of the Soviet regime permitted one church structure in Ukraine during the Cold War period, note that it is only with unleashing of glasnost and perestroika Ukrainian Greco-Catholic Church and Autocephalous Church were able to attain legal status in Ukraine,” Dr. Denysenko said. “Then, the end of the Soviet Era created another opportunity for orthodox plurality in Ukraine.”

Tensions inside the church

“The Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) or UOC-MP refused to participate in December Council, as they claimed the creation of the Ukrainian autocephalous church did not meet canonical norms. While the absence of UOC-MP was disappointing, the process exceeded in the mending of the bitter division of the UOC and UOC-KP that has persisted for the 26 years,” said Dr. Denysenko during the lecture.

In the summer of 2019, the fragile union confronted its first internal challenge as Patriarch Filaret attempted a coup to make him the OCU's patriarch and limit Metropolitan Epiphanius to administrative and external affairs. However, only four bishops joined Filaret in an attempt to “undo” the unification. The other bishops stripped him of any control over the churches and monasteries in Kyiv apart from St. Volodymyr's Cathedral, where he has served for decades.

At that time, the OCU also gained a crucial recognition of two influential churches – when Churches of Greece and Patriarchate of Alexandria announced their recognition of the OCU, Dr. Denysenko said.

Why did Patriarch Filaret attempt the coup?

In 1961, Filaret served in the mission of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) to the Patriarch of Alexandria. He was appointed to several diplomatic missions of the Russian Orthodox Church and, from 1962 to 1964, served as ROC Bishop of Vienna and Austria. In two years, he became archbishop of Kyiv and Halych, becoming one of the most influential hierarchs in the Russian Orthodox Church, where the office of the Kyiv Metropolitan is highly regarded.

At first, Filaret was opposed to church independence. In 1990, he was even a candidate to lead the Russian Orthodox Church but lost the competition to Aleksei Ridiger, who became known as Russian Patriarch Alexy II. After that, Filaret became a promoter of Ukraine's church autonomy, for which Moscow stripped him from the title of Metropolitan of Kyiv and banned him from church service in 1992.

In June 1992, a group of Ukrainian bishops created the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate, which was led by Patriarch Volodymyr (Romaniuk), a former Autocephalous Orthodox Church bishop.

After Patriarch's Volodymyr death, Filaret was elected patriarch in 1995. At that time, some bishops left his church in protest against Filaret and re-created the Ukrainian Orthodox Autocephalous Church once again.

In 2008, Ukraine tried to negotiate with Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew to grant recognition to Ukraine's church, but it didn't come through. Insiders say that a possible reason for that could have been Filaret.

When former President Petro Poroshenko brokered a deal for the Ecumenical Church to grant a Tomos of autocephaly to Ukraine in 2018, one condition was that a new church be created, and Filaret could not lead it.

At first, 90-year-old Filaret agreed to become patriarch emeritus of the new church, which was headed by Epiphanius, his former secretary. But in June, he announced a split from the new church and the restoration of the Kyiv Patriarchate.

Challenges

More than one year after the creation of the OCU, the drama remains, Dr. Denysenko notes. The essential issues causing this dispute lie in four spheres, namely political, ecclesiological, historical, and pastoral.

The political sphere remains one of the most difficult as the loyalties of the Orthodox Church in Ukraine “have frequently been aligned with the significant shifts in the country's political situation.”

Ukrainians themselves were divided over autocephaly, autonomy, and Ukrainization from the beginning. And, for instance, the UOC-MP remains strong even despite the creation of the OCU. According to various media reports, over the past year, 520 UOC-MP churches have switched to the OCU, which now registers 7,000 parishes, 77 monasteries, and 47 dioceses, or ecclesiastical districts.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy hasn't shared much on the topic, only calling on representatives of both churches – OCU and UOC-MP – to engage in dialogue and saying, “faith should unite, and not divide.”

The UOC-KP and UOAC officially ceased to exist on December 14, 2019, when the Ukrainian Ministry of Justice announced their deregistration.

At the same time, the UOC-MP, which does not recognize the OCU as an autocephalous church, continues to function. It also accounts for some 12,300 parishes (according to its figures), but many of the country's most revered Orthodox religious sites remain under the control of the Moscow Patriarchate.

After Poroshenko lost to Zelenskyy, who is neither Christian nor openly religious, the newly created OCU found itself in an uneasy situation. Many parishes decided to wait and see how the situation develops under the new president, experts note. At the same time, governments favouring one church over another “exposes politicians' acknowledgment that the church is a useful instrument of the state,” according to Dr. Denysenko.

Share on Social Media