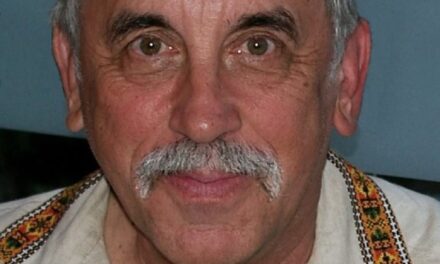

Anastasiya Ringis, Bogdana Torbina

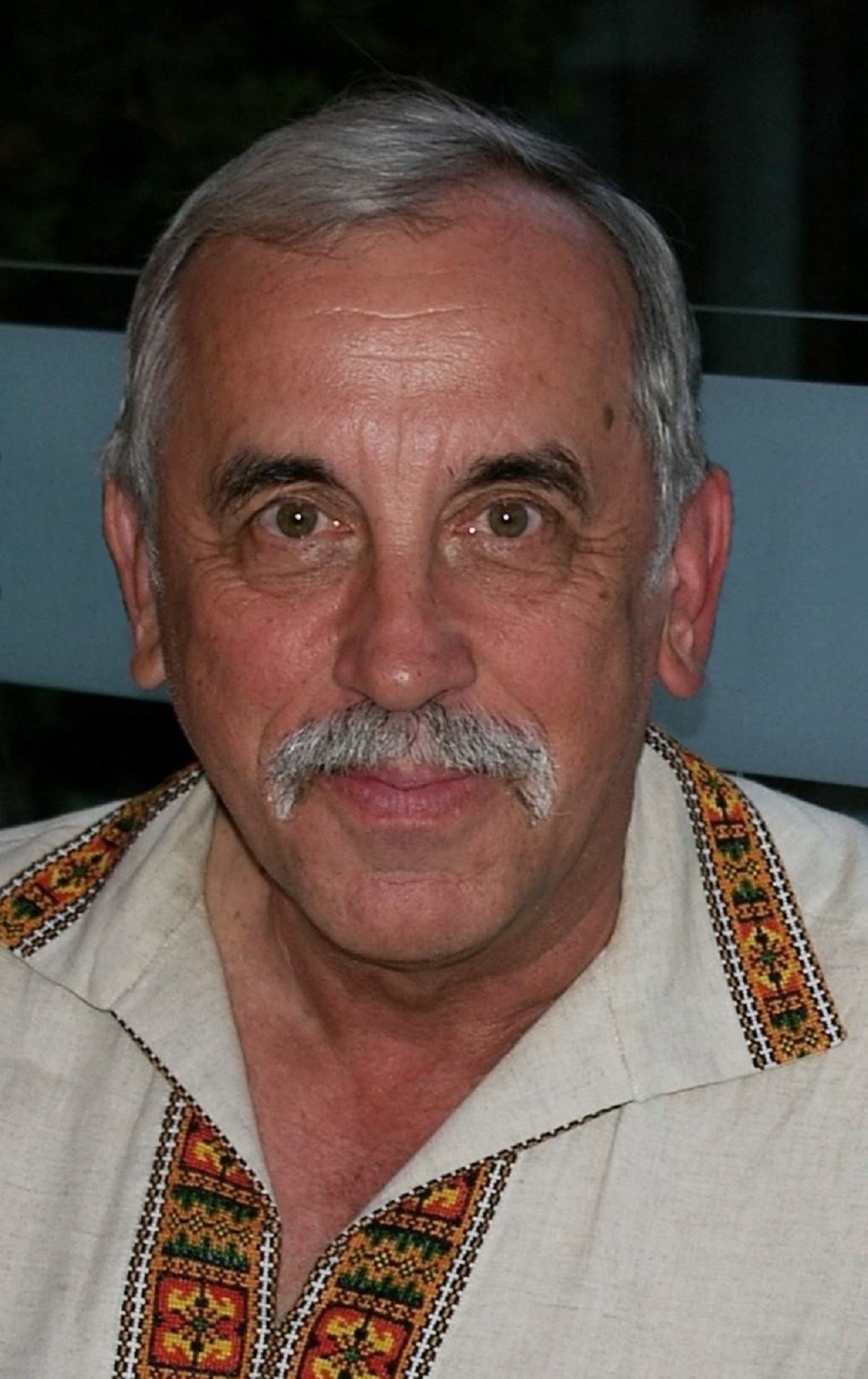

The Nobel Prize award ceremony took place on the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death. The award was presented to human rights activists from three countries, Ukraine, Belarus, and the Russian Federation. One of the Nobel Laureates, head of the Ukrainian Centre for Civil Liberties, is 38-year-old Oleksandra Matviichuk. Oleksandra is well known across Ukraine as the founder of “Euromaidan SOS,” an initiative that protected the rights of protesters during the Maidan Revolution of 2013-2014. The organization fought for the release of dozens of war prisoners from Russian captivity. One of Oleksandra’s most famous cases was the release of a Ukrainian film director, Oleg Sentsov, who spent five years in a Russian prison.

Today, her work revolves around the documentation of war crime cases perpetrated by the Russians against the civilian population of Ukraine. From the start of the war, Oleksandra’s organization documented more than 31 thousand such cases. The pain of the Ukrainian people is her daily work. Although Oleksandra’s work has garnered numerous awards, in real life, she is modest and sympathetic, ready to explain to everyone how human rights violations by one country can impact the global world order.

We would like to understand how human rights activists are doing their work in Ukraine right now.

We work together with other organizations. Our “Tribunal for Putin” network employs over a hundred full-time workers nationwide. Our employees mainly work in the liberated regions. For instance, in the Kyiv Oblast, we see that while the Russians stayed there for only a few weeks, we are still documenting the events, working with witnesses and victims, and collecting testimonies in this region, which was under occupation. We find victims, torture chambers, and mass burial sites in every village. These findings all constitute evidence that the Russians use war crimes as a method of war.

So, are these events not just the result of excessive violence by the perpetrators, but deliberate crimes against the civilian population?

We have been documenting the tortures in Eastern Europe for the last 8 years, and now we are documenting them in the liberated regions of Ukraine. All of this points to the fact that the Russians have instrumented pain. They are trying to break the resistance and occupy the country through the means of unimaginable pain inflicted on the civilian population. They deliberately inflict pain, so that the people lose the strength to resist them.

How do we bring all of the perpetrators to justice? What should the international community do to accomplish this?

The horror that we are now facing in this war that Russia launched against Ukraine is the direct consequence of decades of impunity. Let’s recall that the Russian military committed terrible crimes in Chechnya. They also destroyed entire residential areas from the face of the earth and cleansed the civilian population. Rape, murder, and torture of the civilian population were also widespread. The same crimes were perpetrated by the Russians in Georgia, Libya, Somalia, Syria, and in other countries of the world.

They were never held accountable. And this led them to believe that they could do whatever they wanted. This became part of Russian culture. Russian culture is not Tchaikovsky or Pushkin, but rape and torture. It is a culture of impunity: “I can do whatever I want with a person because the only thing that matters is strength.” In this context, this is not a war of two countries, it is a war of two systems, authoritarianism and democracy. Right now, in this war, the Russians are trying to convince the world that democracy, the rule of law, and human rights are fictitious values because they do not protect anyone during the war and that instead, the only thing that matters is strength. And we need to respond to this, not only for the sake of Ukrainians, but for the sake of the entire world. We need to prove that democracy works and that justice is possible, even if it is delayed in time. Therefore, we must do everything to stop the cycle of impunity and hold Putin, Lukashenko, and other Russian military criminals accountable.

And all the soldiers and officers who committed the horrors.

This is a crucial point, because they should not be able to hide behind the abstract image of Putin. It was not Putin who beat a pregnant woman, whom I interviewed, who begged not to be beaten because she was expecting a child and she was told that her child did not have the right to be born due to her pro-Ukrainian views. All of these atrocities were committed by specific people, so they must be held accountable to the same degree as Putin and the high military command of the Russian Federation, the elite.

Oleksandra, we are amazed by your resilience. Documenting crimes is your daily work. How do you handle it? Where do you find support?

I have been documenting war crimes for the past 8 years. Prior to the full-scale war, I worked with Ukrainians who went through captivity. These are scary stories: murders, rapes, people were trapped in wooden containers, tortured with electrocution, humiliated in every possible way, had their nails cut off, were forced to write with their own blood. But even I, who has worked in the human rights sector for the past 8 years, was not ready for this level of cruelty.

I don’t know how you can even be prepared for this, especially when you are someone with heightened empathy. I personally began working in the human rights sector because of empathy, because I wanted to help people and fight for justice. In the first few months, I forbade myself from reflecting on my feelings. Journalists would ask me which of the stories shocked me the most, and I told them that I do not allow myself to think about that, because you don’t know how you will react, and people need help, not your tears. The first few months, I was fueled with rage.

In your Nobel speech, you said, “we must restore the importance of human rights.” What did you mean?

To be honest, we must admit that the entire civilized world and all countries that call themselves developed have shut their eyes on human rights violations in Russia for decades. Russia persecuted its own civil society, jailed journalists, killed activists, and dispersed peaceful demonstrations. Parallel to this, for decades, the Russian military committed war crimes while Russia used war as a method of attaining geopolitical interests in different countries of the world. And how did the civilized world react to this? It did nothing. Even those countries which called themselves democratic continued to shake Putin’s hand and conducted business as usual. They continued constructing Nord Stream 2 even during the occupation of Crimea and parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts. Therefore, they made Putin believe that human rights values were fictitious not only for him, but for themselves as well because Putin saw that these rights were not being protected. And this is why the voices of our human rights activists from our region were not heard while we said that a country that systemically violates human rights is a threat not only to its own citizens, but to the world as a whole. And Russia is a prime example of this.

And what do we need to do now?

We need to start making political decisions based on the protection of human rights. Not based solely on economic, security, or political interests, but based on the value of human rights. And even if individual countries do this in their domestic politics, they also have to do it in international politics by demonstrating the same loyalty to the value of human rights in international politics. And this is something that we are not seeing because the situation has been taken too far. And those government leaders, who hoped that the problems would somehow vanish, are starting to understand that the issues are not going to go away on their own, that they are becoming more and more aggravated, and that solving them is inevitable.

In your speech, you discussed the architecture of the new world-order. Explain a little bit, how do you see it?

We live under the illusion that we have an international world system of peace and security that has the power to protect somebody. A vivid example is Ukraine, no one is protected there. Take the day that the UN Secretary-General came to Kyiv to meet with President Zelensky, a Russian missile hit a residential building and killed a journalist, Vira Hyrych, in her own apartment. Or the evacuation mission from Azovstal under the UN missions and the International Red Cross which failed to keep medic Viktoria Obidina, who was taken away under these guarantees, from being separated from her four-year-old daughter and thrown into a filtration camp. Neither the UN nor the International Committee of the Red Cross provided effective guarantees. And it turns out that we live in a world in which the protection of human rights and the guarantee of security depends not on international law and the architecture of international organizations, but on whether you live in a country with the military potential of the future, whether your country belongs to some powerful bloc, or whether it has nuclear weapons. And this is a very dangerous world for life. If this logic is supported, it is easy to predict the direction in which humanity will evolve because then, governments will start to invest not in healthcare, not in education, not in some social protection or solutions to global problems like climate change, poverty, or social inequality for instance, but they will invest money into weapons, including nuclear weapons. And this development is very dangerous. Therefore, we need to start repairing the system.

Today’s system was built in the last century following World War II by the winning countries who engrained their unjustified personal preferences into this system which Russia is using right now. And the first step towards reform has to be the removal of Russia from the UN Security Council for the systemic violations of the charter.

You bring to light the human rights violations in Afghanistan, Africa, and other parts of the world. I always wonder how you have so much strength and understanding of the situation.

We live in a very interconnected world and freedom is the only thing that makes our world safer. And our future also depends on how the fight for human dignity will end in Iran and other countries of the world, where at this very moment, people are fighting for their freedom. There are many things that are not restricted within national borders, solidarity and liberty are among these things.

In your speech, you called ordinary citizens to action. What should people do?

I always say two things. First: I understand that people, especially those abroad, who want to help Ukraine can feel a sense of helplessness because the things they can do can look very miserable against the backdrop of the huge catastrophe of the war. But this is not because the efforts are modest and unimportant, but because the call to action is too serious. And I always remember the example from the Maidan, the banner that said “I, a drop in the ocean.” Okay, maybe my efforts are a drop, but this drop is in the ocean. I cannot stop the war, but without my efforts, nothing will change. You can call war a war, you can take part in campaigns or write petitions, and meet with the deputies and officials of one’s own country so that they support Ukraine and provide it with offensive weapons. This choice can be made in everyday life when a payment comes and you understand that Russian gas is cheaper, but you say, “no, I am ready to pay more, because freedom is worth paying more for.”

You were awarded the Nobel Prize along with representatives from Russia and Belarus. What do you think about that?

When you see the news headlines that the Nobel Prize was awarded to the representatives and then follows a list: Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, it reminds you of the old Soviet myth of brotherly nations. Although there are no brotherly nations, there is one nation that dominates, one language that dominates, and one culture that dominates. But we need to understand that this prize is awarded not to countries, but to people who have protected human rights throughout the decades. Human rights protectors from different countries built horizontal connections. These connections are mostly invisible to our society, but we have been working together very closely for a very long time. If we were to draw any parallels with the Soviet times, then it would remind me of the slogan used by dissidents “for your and our freedom.” This is a human history of joint resistance to a common evil that is once again trying to establish itself in our part of the world. I have worked with the Russian “Memorial” and Belarus “Viasnaya” for many years. And in the past 8 years, these were one of the first whom I constantly turned to for help with cases of Ukrainian political prisoners – the “Memorial.” And they never turned me down. Many helped me with specific cases, even under the conditions of the Russian authoritarian regime. This is actually exactly why they are banned in Russia. Ales Bialiatski is behind bars. Because they always called the war a war, voiced that the occupation of Crimea is a crime, and did not simply talk, but supported their positions with active actions. Unfortunately, they are the minority in Russian society. The named colleagues voice their opposition not only against the authoritarian regime, but also against the dominant narrative in Russia. It is a shame, but the majority of Russians support the war, because they have an imperial mindset. They see Russian greatness in the forced reconstruction of the Russian empire, which is of course, dangerous for other nations.

How has the Nobel Prize changed your life? Do you now have more opportunities for the advancement of Ukraine’s interests?

I will say right away that we did not expect to receive the Nobel Prize and that this was a huge surprise. We did not know that we were nominated. And to think that we would win a Nobel Prize was clearly not in our thoughts. Therefore, we were not prepared for such a stream of attention and curiosity. On the one hand, to be a Nobel Laureate is a separate job, on the other hand, the Ukrainian voice of human rights activists can finally be heard. We used to be heard at the UN committee on human rights or at the OSCE meeting, but clearly not in those halls where political decisions were made. However, the Nobel Peace Prize did end up giving us the opportunity to make the voice of human rights protection more meaningful.

Share on Social Media