Rachel Caklos for NP-UN.

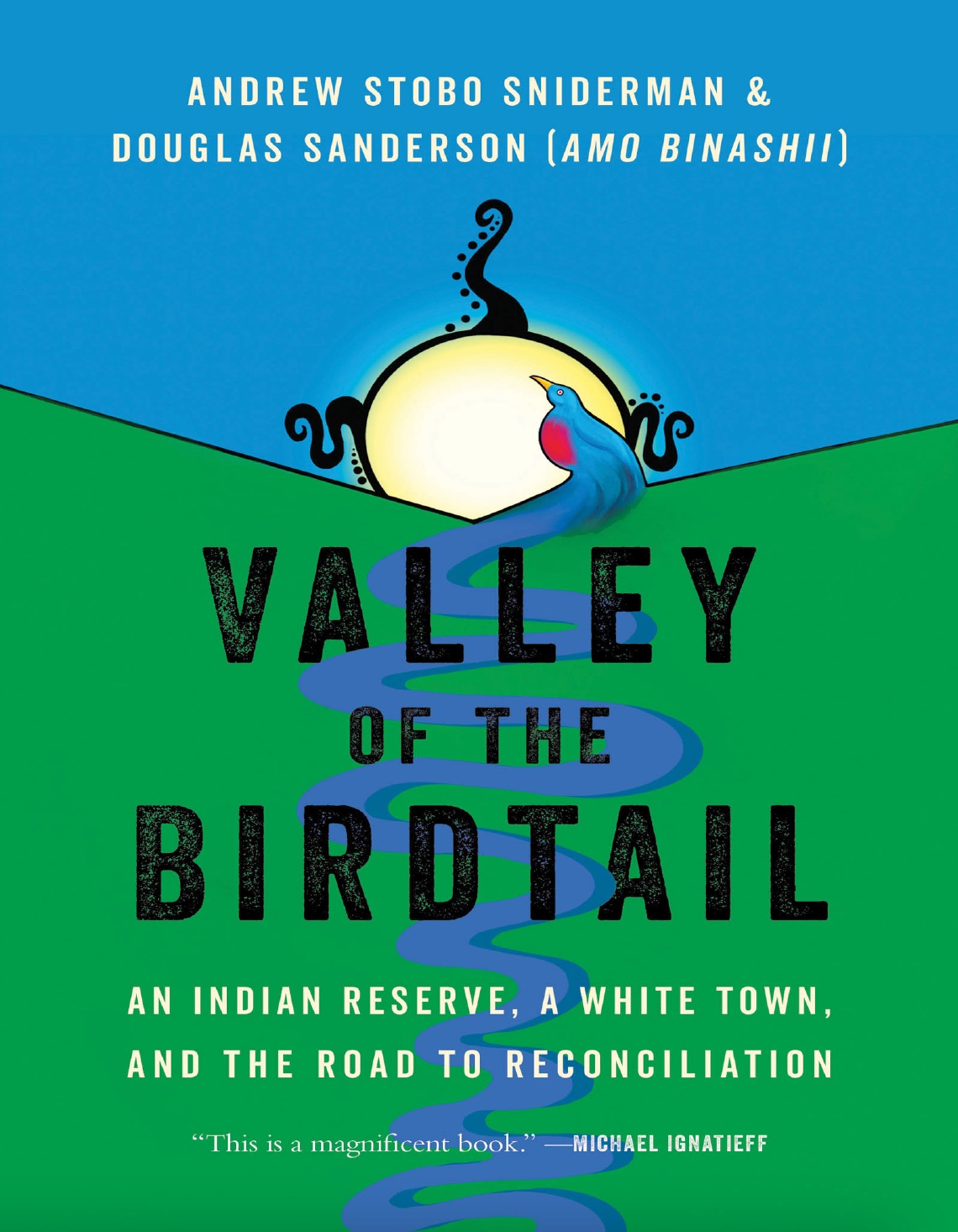

The Valley of the Birdtail, written by Andrew Stobo Sniderman and Douglas Sanderson (Amo Binashii), is an extraordinary book addressing the connections between two neighbours, an Indigenous reserve, and a Ukrainian immigrant community, separated by the Birdtail River in Manitoba, Canada. This work has been nominated for the KOBZAR™ Book Award, recognizing works that contribute to Canadian literature, demonstrating a connection to the lives of Ukrainian Canadians. This award from the Shevchenko Foundation has provided the opportunity for recognition and funding for authors to uncover stories and disseminate the cultural history of Ukrainians in the Canadian context.

The co-authors are a duo that both came to the project with a curiosity to learn and uncover the relationship between the two residing communities while uncovering the truths of hardship, oppression, and the realities of their differences. The true stories present this historical relationship that runs alongside the development of Canada as a young country and uncovers the contemporary position and understanding of Indigenous Canadians and the structural inequalities and racism that still exist today.

This concept flourished from a magazine article Stobo Sniderman had written for Maclean’s Magazine as a University of Toronto law student in 2012. He was curious about the differences between the schools on reserve that were underfunded and incomparable to the perfectly good public schools on the other side of the river. He wanted to understand how this could be and why there were such stark differences, and believed that the best way to truly understand the situation was to experience what it was like to live on both sides of the divide.

After flying to Manitoba to visit the Valley of the Birdtail and the communities of Waywayseecappo and Rossburn, he knew there was a story to be explored. With his time in the area, he realized Rossburn was home to a large Canadian Ukrainian population and was curious about their arrival and settlement there.

With an exciting opportunity to dig deeper, Stobo Sniderman reached out to his former Professor, Douglas, who grew up in various parts of Western Canada and has personally experienced the connection with Ukrainian communities and their culture.

In an interview I conducted with the authors, Andrew described the book as a great example of how little neighbours know about each other and how possible it is to spend one’s whole life as a neighbour to an Indigenous community and not know anything about it. As the two communities have been living so close to each other for a long time, it requires exploring and understanding the truthful histories of their settlement, their engagement with each other, and the historical lens of Canada’s governmental involvement with both groups. Andrew explained that the Ukrainian Canadian segment of the book is crucial because it shows how much they share with their Indigenous neighbours without being aware of it.

Douglas brought a great perspective to the conversation, as he did not see the divide between the two groups. He is a member of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation and, throughout his professional career, has done fantastic work engaging Indigenous issues within the topic of policy. Growing up in the farming communities across the prairies, he was interconnected with Ukrainian families and their culture. He reminisced on the memories of the dessert perogies he enjoyed many times before he moved away to British Columbia for high school.

Douglas expressed that he came into the project with a strong sense of the Ukrainian backbone of the country, which he described as “incredibly powerful” within the prairies, including towns like Vegreville with the enormous Ukrainian Easter Egg on public display. However, he was surprised at the level of his connection to Ukrainian Canadians and how pervasive it was. Yet, he never stopped and questioned why they were there.

When the war started in Ukraine, it made him realize that no one was asking why or how these strong Ukrainian Canadian roots came to be, therefore, it pushed them to learn about the backstory of Ukrainian immigration and the efforts of the Canadian government to make that immigration happen. Douglas explained that many policy initiatives that went into settling that population and ensuring that they had access to the kind of economic and educational opportunities that allowed those communities to thrive was something that he had never understood before. By participating in the book, Douglas could connect himself to the histories of Ukrainians in Canada in a unique and new way.

A significant consideration for both authors was ensuring the proper expression of the valiant story of Ukrainian immigration to Canada. Andrew and Douglas ensured to tell the reader about the struggle and determination of the community and allowed Ukrainians to feel a sense of pride. They want the community to feel seen and heard and give credit to a compelling story of overcoming hardship and thriving. In connection with the Ukrainian background and stories of the book, Andrew and Douglas discuss the issues between the two communities and how they fail to understand or look beyond the surface and question their inferences as to why things are the way they are.

Chapter 7, The Young Napoleon of the West, introduces men involved with the Canadian government to increase immigration to Canada. Clifford Sifton, a Manitoban, was a prominent figure who worked alongside the Wilfrid Laurier Liberal government in 1896, where he became the minister of the interior, giving him the prerogative to find people to settle and work in the prairies. The authors later inform the reader of the Ukrainian history in Europe and how they were called pigs by others and were restricted from their culture, language and even Ukrainian schools. These restrictions continued to bleed into everyday life as marriage without permission was not allowed, the use of the words “Ukraine” and Ukrainians” were banned, and in 1863, the use of the Ukrainian language was prohibited by Russia. This oppressed situation saw light when Canada called Ukrainians to its lands, where Sifton sold this “Canadian Dream” by giving immigrants free land. Between 1895 and 1914, nearly 180,000 Ukrainians immigrated to Canada. People were desperate to leave Ukraine and start a new life away from the oppression of Russia; however, the story did not change for the better that quickly.

As Ukrainians settled, they were not easily accepted. The authors perfectly present this perspective with a quote from a Rossburn local. They said:

“I don’t like . . . the way they always stick to themselves,” … “They don’t seem to want to mix, no matter how hard you try to make them welcome.” Another said, “They still live like pigs with their huge families,” “always jabbering away in their own language.” “They just don’t live like white people,” a Rossburn resident said. – Page: 158

By the 1940s, these communities faced a harsh divide as they were deemed “too different” from the already settled population. Ukrainians experienced many challenges upon arriving and settling in Canada. Discrimination was a powerful force, affecting their ability to function within society, specifically with their economic power imbalances. The Ukrainian people understood that this discrimination was not going to go away and that they were never going to be accepted as equals. However, even with these challenges, the Ukrainians held true to their identities and cultures because, as one expressed, without them, they are nothing. Therefore, this deep understanding of Ukrainian history, the importance of their culture and how life was in Canada is vital in understanding the deep roots of Ukrainian influence within Canada.

“De nema boliu tam nema i zhyttia” (Without pain, there is no life).” – pg. 156

While maintaining a strong story of the Ukrainian immigration to Canada and the many challenges they faced before and after their settlement, Andrew and Douglas aimed to situate it against the actual historical and economic background of the community across the river. The authors underscored the significance of a heroic and compelling story; however, it cannot be used to discount the reality of other people’s situations or ignore the differences in access to opportunities.

Some of these factors, such as access to opportunity, funding, societal treatment, awareness, and access to commonly used products like credit, are being trimmed out at the outset for Indigenous communities. Douglas further explained that something as common as credit is inaccessible to Indigenous communities. He explained, “when you start showing the reality of the burden that Indigenous people have had to carry, then I think it puts their stories into much more context.” This was a significant focus of the book, and it was done perfectly with a balance between utilizing the stories of the two groups of people and recognizing their differences through opportunity and acceptance within society.

One of the most potent parts of the book I found was that in 1936, the Governor General of Canada, Lord Tweedsmuir, came to the Ukrainian community and acknowledged their culture and successful growth within Canada. In a speech at a community event, he praised the Ukrainian community for their “valuable contribution” to the young nation. He said they had fulfilled their part in becoming Canadian citizens while accumulating the privileges and rights of such status. The Ukrainians were able to indulge in their culture through song, dance and food and their community was celebrated for bringing multi-culturalism to Canada. In contrast, it was illegal for another 15 years for Indigenous communities to engage with their culture freely and to be able to dance and participate in their own culture through ceremonies.

This connection brings a compelling understanding of the historical timeline within Canada and demonstrates the restrictions placed on one community and not the other. Another thought-provoking timeline point would be the publishing of the Canadian Mosaic by John Murray Gibbon in 1938, which fostered a new perspective on immigration that later positively shaped Canadian immigration policies.

The embrace of Ukrainians shows the best of Canada, and it was one of the first starting points in the discussion of multiculturalism within the country. Yet, with this celebration on one side of the river, we continue to oppress the community on the other side.

Valley of the Birdtail is a striking book that presents the reader with an array of historical contexts that capture the inspiring story of Ukrainian immigration into Canada and provide a representation of the struggle that every Ukrainian Canadian knows about, especially as the battle continues in light of the current war in Ukraine. However, within the Canadian context, the authors ask their readers to set this story against another story of struggle happening simultaneously and to hear them both in tandem. Douglas emphasized that it is “too easy to say that those of you who have not succeeded, it must be because you are doing something wrong. That is the instinct we are trying to attack with this book.”

I can highly recommend this book to anyone curious to know the deeply rooted histories of both Ukrainian and Indigenous communities in Canada as they tackle very challenging topics and present the readers with the harsh realities Indigenous communities have faced, including residential schools and the intergenerational trauma that runs through Indigenous individuals and their communities.

The book does a thorough job of outlining the history of Ukrainian immigration from Ukraine. This book successfully balances the two very different communities and makes readers stop and think about what we commonly take for granted in contemporary Canada.

In a speech performed at a university commencement, J.B. Pritzker presented a powerful thought on empathy, kindness and the engagement of cruelty against others, which I resonate with in connection to the engagement of residential schools and treatment of Indigenous communities in Canada, as well as the continuous struggle faced by the Ukrainian people. He said,

“We survived as a species by being suspicious of things that we aren’t familiar with. In order to be kind, we have to shut down that animal instinct and force our brain to travel a different pathway. Empathy and compassion are evolved states of being… I’m here to tell you that when someone’s path through this world is marked with acts of cruelty, they have failed the first test of an advanced society. They never forged new mental pathways to overcome their own instinctual fears. Over the many years in politics and business, I have found one thing to be universally true, the kindest person in the room is often the smartest.”

– J.B. Pritzker

Thank you to Andrew Stobo Sniderman and Douglas Sanderson for contributing to this article. You have made a piece of work that will last in the hearts of your readers forever.

Rachel Caklos is the winner of UCU’s New Pathway 2023 Scholarship

Share on Social Media