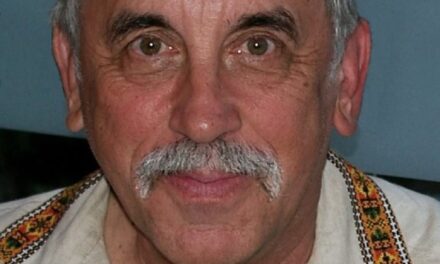

Yuri Bilinsky, New Pathway – Ukrainian News.

In the quest to remove the stumbling block for full-blown development of renewable energy, the problem of durable and cheap stationary electricity storage, Donald Sadoway is the universally recognized leader. He has promised to deliver an alternative to lithium-ion batteries, which, he claims, have approached their limit in terms of cost per kWh and dependability.

Sadoway's start-up company Ambri, which has sprung out of his MIT liquid battery lab, has been working on the battery technologies since 2011. The novel approach has attracted around $65 M in angel investment from the likes of Bill Gates and an energy multinational Total, has taken a couple of turns but now Sadoway has confirmed his recently announced plan. In his interview to NP-UN, he said that Ambri is on course to delivering its first commercial stationary liquid metal battery in 2020. The world of energy will likely never be the same after that.

In the new chapter of our series “Ukrainian Diaspora Science Hall of Fame” (Donald Sadoway is a Canadian-born son of Ukrainian parents), NP-UN’s Yuri Bilinsky spoke to Sadoway about his plans.

Bilinsky: Last year, you announced that Ambri would deliver its first commercial battery in 2020. Does this plan still hold?

Sadoway: Yes, the first battery is still destined to be released by the end of 2020. We are doing something for the first time, so it could slip into the first quarter of 2021. But we need to get that first product into customer’s hands soon because otherwise people are going to grow impatient and the company could be at risk of folding.

Bilinsky: Is it going to be the same battery that was shown on CBC in December 2018?

Sadoway: What was shown on CBC was a battery that was tested and worked. But what we are preparing now is a different battery, it was never shown before. It’s same size but different cell chemistry which we switched to in 2017. It’s very different from what we had before and we made these changes to respond to the falling price of lithium-ion batteries which some people see as a threat to us. Our current chemistry is even cheaper than before. We’ve had to take a few steps back to become familiar enough with the idiosyncrasies of the new chemistry. We’ve learned a lot along the way, we couldn’t have gone to this new chemistry back when the company was formed in 2011. There are certain things about this new chemistry that we didn’t know even coming out of MIT.

Bilinsky: Has the lithium-ion technology developed so significantly that you’ve had to design a new chemistry?

Sadoway: No, the lithium-ion’s chemistry is unchanged from what it was ten years ago. Its price is falling not because of new discoveries in the chemistry of it, it’s just brute force by the Chinese who’ve figured out how to manufacture it more cheaply. They are doing to lithium-ion batteries the same thing they did to the solar panels. They are still making polycrystalline silicon photovoltaic cells. But the price of solar energy now is ten percent of what it was ten years ago because the Chinese have cut the manufacturing costs. The price of lithium-ion cells has come down by a factor of ten as well for the same reason. But it’s not the battery for large-format deployments. The battery to power a sub-division of, say, 200 homes will contain a hundred thousand of these little lithium-ion cells which will require interconnection, power electronics and air conditioning because those cells sitting in a close proximity to each other will heat each other. And if that temperature rises to about 65 degrees Celsius, the cells could burst and catch fire. The whole notion of using lithium-ion batteries for stationary storage still needs verification. No one is freely buying lithium-ion batteries for this application, there are only government-funded demonstrations. But that doesn’t matter. Investors see the price of lithium-ion falling and turn to us, “What do you guys have? You are toast.” So, we had to respond. In a sense, it made us better. I don’t think that that threat was real but it required us to be even smarter.

Bilinsky: Was your previous technology cheaper than the lithium-ion technology now?

Sadoway: Yes. But people were looking at the trend of the lithium-ion cost and thinking that if that trendline continues in the same way, it could drop from USD250/kWh in 2017 to USD150/kWh. That was below our projections.

Bilinsky: What is your expected cost?

Sadoway: At scale, our cost is going to be below USD100/kWh. By the way, that’s not the cell cost, it’s all-in, at the battery level. I don’t think they can beat that.

Bilinsky: You referred to government-funded demonstrations of stationary lithium-ion batteries, like the one Elon Musk’s Tesla installed in Australia. How are those progressing?

Sadoway: That facility’s numbers are shocking. They put a 100 MWh for USD50M, that’s USD500/kWh. If you look anywhere, the cost of lithium-ion energy storage is being reported as below USD200/kWh. I called Bloomberg New Energy Finance and asked what was going on, something didn’t add up. Their graph says that “pack price” was below USD200/kWh in 2018, so, why did South Australia just pay USD500/kWh? No one is buying these batteries freely, no power company is voluntarily buying them because they are too expensive. Also, lithium-ion batteries degrade as we all know from our computers and cell phones. You can’t put something like that on the grid where they expect a battery to last minimum ten years and would happily have 20 years. No one has a 20-year old rechargeable battery. That’s what we are building for the first time.

Bilinsky: You have a customer who is willing to pay for your first battery. What industry is this customer in?

Sadoway: I can’t disclose this. They’ve given us the specifications that we have to meet. If everything works the way we expect, that customer will want to buy everything we are producing and they don’t want to tip off their competitors.

Bilinsky: Lithium-ion batteries are said to work for up to four hours. How long do your batteries last?

Sadoway: We can tailor the performance of the battery to meet different applications. Imagine, you have it in conjunction with solar. After the sun goes down, you provide continuous electricity for four hours. In some other applications, it needs to be longer, eight or twelve hours. We could tune the battery for that, we just need to use more cells. Our batteries can also work in short bursts, about 15 minutes, for example in frequency regulation. There is a tuneability of the output. Our batteries could be used in different settings, residential or manufacturing. We’ve been talking to an auto company for example, they would like to run their manufacturing facility on 100% renewable energy so that they could say that their cars are made with no burning of fossil fuels. We have very keen interest from the U.S. military who would like to get their bases off the civilian grid for security reasons. There was a power black-out five years ago in San Diego which took down the Miramar naval base. It takes about 15 minutes for the diesel back-up to kick-in, which is not acceptable.

Bilinsky: Have you ever talked to Elon Musk or anyone at Tesla about your technology?

Sadoway: No. Elon Musk is interested in building cars and this battery has no utility in a moving vehicle. As to stationary use, he is heavily invested in lithium-ion. He is also behind Solar City and he reasoned he could sell solar panels in conjunction with batteries and he already has a battery plant making lithium-ion. Businesses that use batteries want something turn-key ready, they are not interested in taking a chance on a new technology that may or may not succeed in the market. There is a whole bunch of start-ups offering radical innovation in batteries but none of them has succeeded. It’s very difficult to break into this market because the performance requirements are so demanding and the price point is so low. It’s the worst combination. General Electric in 2006 decided to go into the stationary storage, in the old Zebra (liquid sodium nickel chloride) chemistry. They spent ten years and it must have cost them about $1B because they had 250 people working on this thing and built a manufacturing facility in upper New York state. After ten years, they quit because they could “not manufacture the batteries at a competitive price point compared to other battery technologies.” I assume that this means they were undercut by the falling price of lithium-ion.

Bilinsky: If this market is so difficult, how have you been able to find a customer?

Sadoway: This customer does not believe that lithium-ion is long-term viable in stationary applications. They have been looking everywhere and have seen everything, they didn’t come to me because they saw my TED-talk. And they think that the liquid metal battery is the most sensible.

Donald Sadoway’s background:

Donald Robert Sadoway’s maternal grandparents came to Canada from Ukraine right after WWI. His mother, Orysia Romanko, was born in Ukraine in 1920 and came to Canada as a three year old girl. In 1910, his paternal grandparents came to West Fort William, now Thunder Bay, where his father, Donald Anthony Sadoway, was born. The family moved to Toronto where Sadoway’s parents met. Donald Robert was born in Toronto and the family moved to Oshawa when he was three years old. He came back to Toronto to attend the University of Toronto for his undergraduate and graduate studies, ultimately earning his PhD. Sadoway was active in youth groups and became the president of the Ukrainian Students Club at U of T. He served as vice-president of SUSK (Ukrainian Canadian Students’ Union) for several years.

An orthodox Christian (pravoslavnyj), Sadoway was a choir director at the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Boston, Massachusetts.

Bilinsky: In one interview you said ‘You don’t want to hear me sing’ but it appears that you were a choir director.

Sadoway: I was a choir director and of course I knew how to sing but I don’t consider myself to be a fine singer. It’s one thing to conduct, it’s another thing to perform. My daughter on the other hand has a Master’s degree in opera voice.

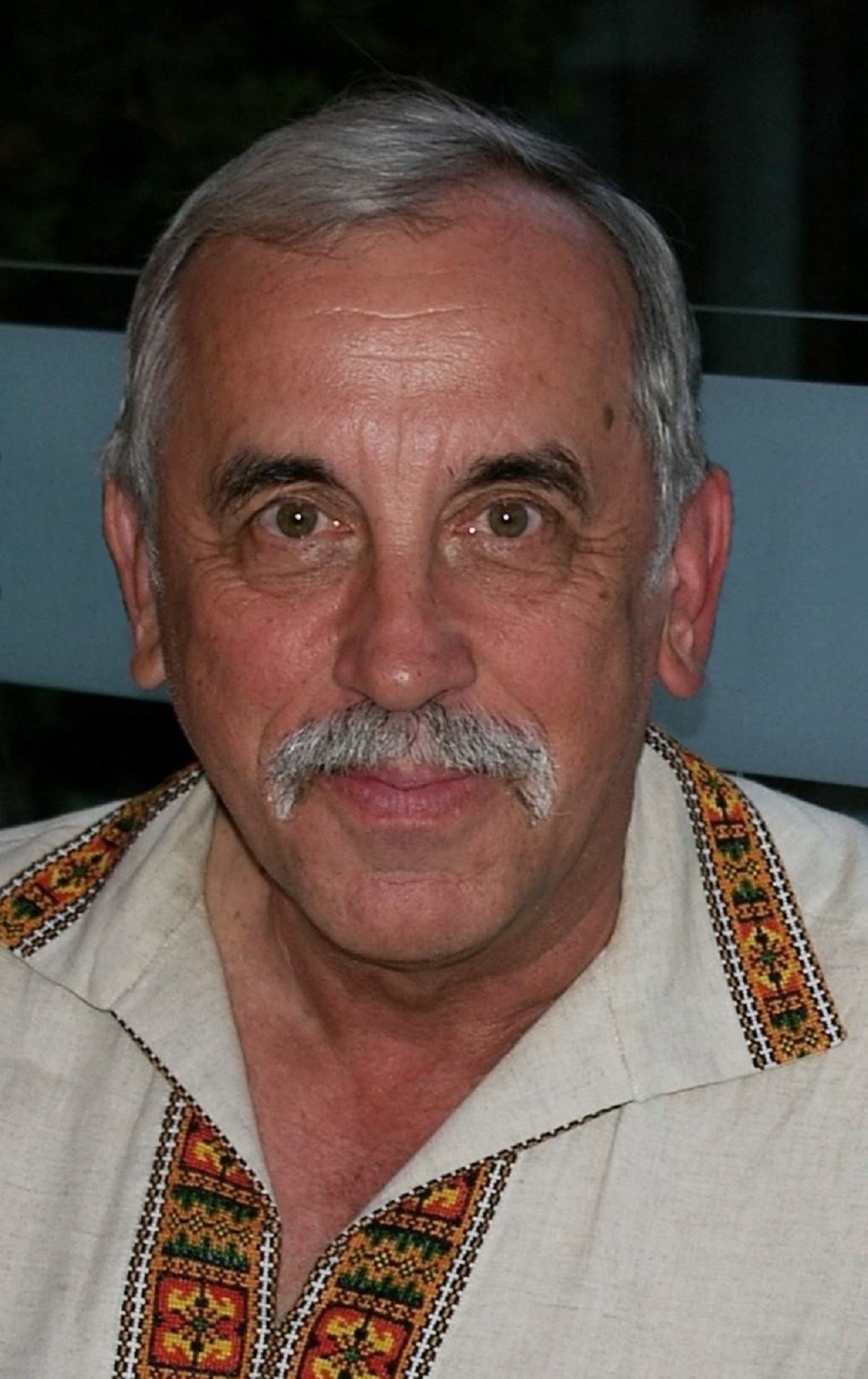

Sadoway has visited Ukraine several times, starting with his visit to Kyiv in 1990 when he gave a lecture in Ukrainian at the Institute of General and Inorganic Chemistry. While in Lviv, in June 2018, for a metals conference, he met his younger son’s full namesake, the city’s Mayor, Andriy Sadovyj (in the photo).

Sadoway: Although I speak ‘kitchen Ukrainian’, when I stay in Ukraine for a week, the language comes back.

Donald Sadoway (left), Prof. Ganna Stovpchenko (centre) and Mayor Andriy Sadovyi during the conference in Lviv in 2018

Share on Social Media