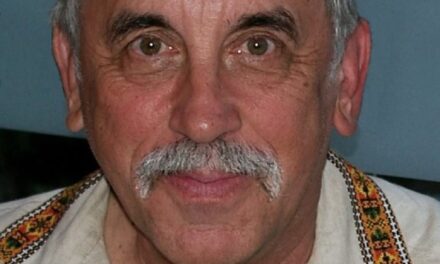

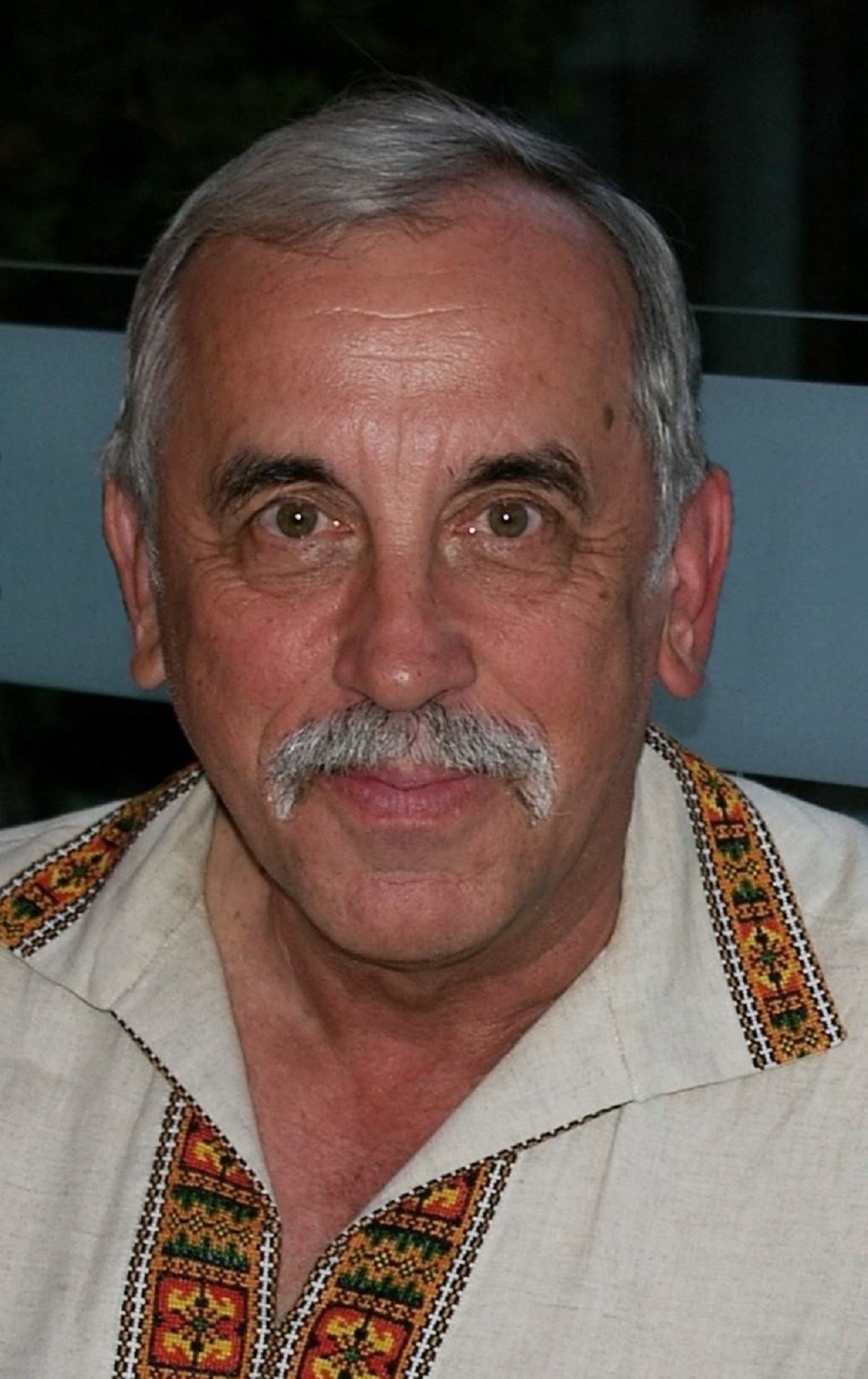

Andrij Makuch for New Pathway – Ukrainian News.

Dr. Serge Cipko, Assistant Director, Research, at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (University of Alberta), spoke to a Toronto audience on April 12, 2018, regarding his recent publication, Starving Ukraine: The Holodomor and Canada’s Response, published by the University of Regina Press. The book, which draws extensively on Canadian newspaper accounts from 1932 to 1934 and archival sources, examines the state of knowledge about the Famine in Ukraine in the Dominion at this time and the reactions to it. The event was sponsored by the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium (HREC) at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (University of Alberta), together with the Shevchenko Scientific Society of Canada, the Buduchnist Credit Union Foundation, the Canadian Foundation for Ukrainian Studies, and the Canada-Ukraine Foundation.

Dr. Cipko began by discussing an open letter sent in 1962 by Michael Luchkovich, the first Ukrainian Member of Parliament in Canada, to US Secretary of State Dean Rusk. In it Luchkovich mentioned the “shocking” lack of regard that had been paid to the “millions of Ukrainian peasants” who died in the “Communist inspired famine of 1932-1933,” while taking Rusk to task for his department’s exclusion of Ukraine as a country designated for support as one of the “subjected nations of Eastern Europe.” Dr. Cipko noted that this was not the first time Luchkovich had raised the famine issue—as an as an MP he had addressed Parliament on the matter in a February 1934 speech.

Dr. Cipko then provided examples of mainstream Canadian newspaper articles of the day dealing with famine in “Soviet Russia.” Even though a dire crisis situation was the most common interpretation of events in the Soviet Union, there were also alternative accounts denying or diminishing hunger and starvation in the USSR, leading occasionally to confusion or inconclusive opinions on the matter.

The Mennonite press in Canada carried numerous articles citing letters relatives had received from family in Ukraine, who told of their increasingly alarming food situation there. This was a major impetus for the raising of the famine issue in the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan by Rosthern MLA John M. Uhrich on March 15, 1933, which resulted in the passage of a resolution urging the Canadian government to offer food and cattle to the Soviet Union on a barter basis to alleviate the conditions of hunger there.

Dr. Cipko spoke about coverage of the Famine in the Ukrainian-Canadian press and about the numerous public meetings held to protest the Soviet assault on the Ukrainian peasantry. He reckoned there were around 80 such gatherings in Canada, organized predominantly but not exclusively by Ukrainians. Dr. Cipko dealt specifically with two such gatherings, one in Krydor, Saskatchewan, in March 1933 (attended by 250 people) and another in Dauphin, Manitoba, in October 1933. The latter appealed “to the opinion of the civilized world” to “force the Soviet Government to cease this inhumane policy of starving out the population of … Ukraine.” Cipko added a note that a large-scale Ukrainian reaction in Canada to the Famine was fairly late, partly because initially the scope of the catastrophe was not completely evident.

The Dauphin protest meeting took note of the recommendation of the League of Nations that the only realistic course of action was for groups “to address themselves to organizations of a purely non-political character such as the International Red Cross.” Cipko remarked that, in fact, Ukrainian farmers had already attempted this in the Hafford, Saskatchewan, area in 1932. They approached the Canadian Red Cross to arrange the sending of 400,000-500,000 bushels of wheat to Ukraine, but they had been turned down following a Soviet claim in September-October 1932 that the purported dire conditions did not exist in Soviet Ukraine.

Dr. Cipko noted that there was considerable support for the Soviet Union in the early 1930s among the Left in Canada. As a result, charges of intentional large-scale famine in the USSR tended to be dismissed or deflected. A common counterpoint offered was that only a relatively small number of not so innocent “kulaks” were suffering the most, obstructing the path to a brighter future by opposing the progressive Soviet collectivization campaign: “What are 1,000,000 in a population of 162,000,000?” According to Cipko, the Sovietophile Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association’s newspaper Ukrainski robitnychi visty carried articles such as “Why Don’t They Help the Starving of Western Ukraine?” (deflecting the issue) and “Who Does Not Work, Does Not Eat” (rationalizing depriving foodstuffs from those not supporting the regime).

Dr. Cipko noted that some of the Famine protests in the larger urban centres of the United States, notably New York and Chicago, had resulted in violence following their attacks by pro-Soviet elements. In Canada, the only known attack of this kind occurred in Winnipeg on July 16, 1933, when a meeting at the Prosvita Reading Hall seeking to set up a Ukrainian National Council that could provide a united response to the Famine was violently disrupted. Dr. Cipko also provided a later account of the incident written by its chairperson, Stephen Skoblak.

One of the main takeaways from the presentation was the fact that much more information about the Holodomor appeared in the contemporary Canadian press than has commonly been assumed, albeit with various counterpoints. As such, the Famine was not unknown but, rather, something that had faded from public memory. A second key point Dr. Cipko showed was the extensive mobilization of the Ukrainians in Canada at that time to protest the starvation in Soviet Ukraine, demonstrating the vitality of the community of the day.

Share on Social Media