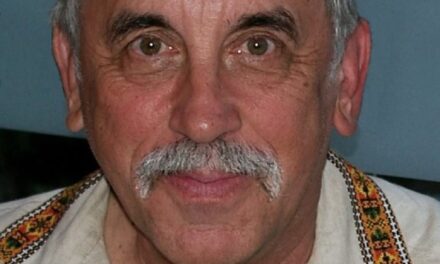

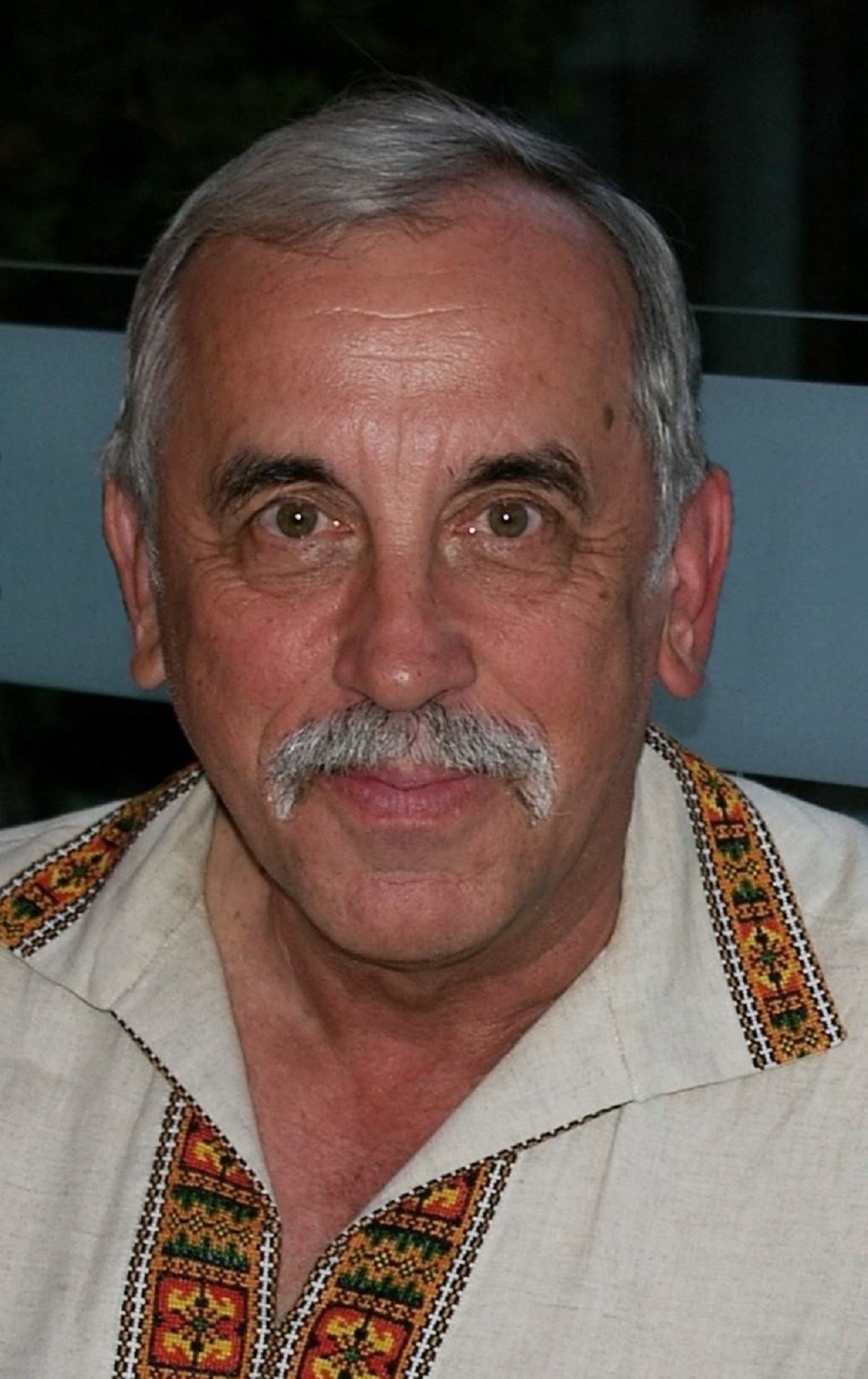

Gord Yakimow, Fraser Valley, BC.

The Holodomor of 1932-1933 was a wretched crime perpetrated upon the Ukrainian people by the Soviet regime of Josef Stalin. When the Ukrainian peasantry resisted Stalin’s policy of collectivization and industrialization, the regime responded by rounding up approximately one million Ukrainians and shipping them off to Siberia (where many died), by applying impossible grain quotas which denied the Ukrainian peasant food that he himself had produced, by bringing in brigades of armed activists from elsewhere in the Soviet Union (the despised “Moscalee”), thugs who terrorized the villages and confiscated anything which resembled food, and by imposing a system of internal passports which made it illegal for those who were starving to travel in search of food. The phenomenon has come to be known as the “Holodomor” … from the Ukrainian words “golod” (hunger) and “moryty” (death).

How many died of starvation in 1932 and 1933? Reports vary. Maybe as few as 2.6 million. Maybe as many as 10 million. Maybe fewer. Maybe more. What is irrefutable is that a deliberate policy of genocide perpetrated by the Soviet regime of Josef Stalin resulted in the death by starvation of a great many Ukrainians: men, women, children, babies.

The Holodomor was largely unknown outside the frontiers of Ukraine for many years. Stalin made it a crime punishable by death for a Soviet citizen even to hint of the famine in Ukraine. Western governments ignored reports of the despair in Ukraine, not wishing to jeopardize lucrative trade agreements with an industrializing Soviet Union. Duped (or bought) journalists from publications as prestigious as the New York Times sent reports which ignored the reality of what was occurring in Ukraine.

However, with the attaining of independence in 1991, and especially with the election of Viktor Yushchenko following the Orange Revolution of 2004, the Government of Ukraine began a campaign to educate its own population, and the people of the world, about the Holodomor. Memorials were created in many of Ukraine’s cities. Thousands of secret documents pertaining to the Holodomor were declassified. In November of 2006 the Verkhova Rada (Ukrainian Parliament) passed a resolution recognizing the Holodomor as a deliberate act of genocide, and making illegal any statement of denial. A “Holodomor Remembrance Day” was declared.

Other nations quickly followed suit. In November of 2003, the United Nations approved a resolution which recognized that between 7 and 10 million Ukrainians died, “victims of the cruel actions and policies of a totalitarian regime.” And in April of 2010, the Council of Europe (part of the European Parliament) declared that: “Stalin’s regime was guilty of the Holodomor famine that killed millions in the 1930’s.” In 2008 a Holodomor Memorial Flame, lit in Kyiv, traveled through 33 countries (including 23 cities in the USA) to commemorate the 75th anniversary of this human tragedy.

Canada has done its part in ensuring that the atrocities of the Holodomor will not be forgotten. The world’s first Holodomor monument was unveiled in Edmonton in 1983, on the fiftieth anniversary of the genocide. Since then monuments have been unveiled in Calgary, Winnipeg, and Windsor. The Parliament of Canada, in May of 2008, passed a private members bill – Bill C-459 – declaring: “Throughout Canada, in each and every year, the fourth Saturday in November shall be known as ‘Ukrainian Famine and Genocide (Holodomor) Memorial Day’.” Other countries have passed similar resolutions recognizing the Holodomor, including Australia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Ecuador. A Holodomor monument was erected in Washington, DC in 2015.

#

There are numerous Holodomor memorials in Ukraine. In Ternopil the memorial is built into an arched stone entranceway. The grey entrance is blocked. A grey board has been bolted across the blocked entranceway. The dates “1932 -1933,” gold on grey, are attached to the board. Beneath the board is a stylized sheaf of wheat. The memorial is on a busy street in the centre of the city, where thousands of pedestrians pass by every day. It is attached to an outside wall of the green-domed Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral, or Sobor. As I stood before the memorial, a steady drizzle fell from the grey sky. At the base, cemented into a pile of rocks that are suggestive of skeletal skulls, is a brass plaque, gold on grey, upon which are two Ukrainian words which state: “To the Victims of the Holodomor”.

In Zaporizhzhya the memorial is built beneath powerlines on a busy road where many people drive by, but few walk. A white cross is attached to five grey granite blocks piled one above the other. A white statue of a slender, barefooted woman stands on a marble base beneath the cross. Looking aimlessly to her left, she presses against her thigh one stalk of a full head of wheat. Etched into a grey-black marble plaque at the base of the cross are the words (in Ukrainian) “To the Victims of the Holodomor 1932-1933.”

Kyiv’s St. Mikhayil’s Square is a place of magnificence in a truly beautiful city. The golden domes and sky-blue walls of the monastery frame one side of the square. An imposing and impressive government building, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, frames a second side. A third side of the square is open, offering an unimpeded view of the magnificent St Sophia’s Cathedral. In the square is a dramatic anachronistic statue of Princess Olga. She is one of Ukraine’s heroes: her grandson was Volodymyr the Great, who in 988 AD brought Christianity to Ukraine, and her great-grandson was Yaroslav the Wise, who united Ukraine under his enlightened leadership; his remains lie in St Sophia’s, which he built. Princess Olga looks slightly to her left … towards the main entrance to the monastery.

Beside that main entrance to St Mikhayil’s Monastery of the Golden Domes is a small, enigmatic memorial. It is powerful in the complexity of its simplicity. In it is the Christian cross of the Ukrainian cossacks. In it is the Madonna, the mother of Christ. In it is a despairing mother, her hands spread in bewilderment and grief. In it is a starving baby, pressed against the breast of an anguished mother who can provide nothing for her child. In it is a broken heart. In it are the bones of the dead. In it is a crucified Christ … and perhaps a crucified nation.

On the side of the monument is a simple plaque which reads, both in Ukrainian and in English: “For the Millions of Ukrainians – Victims of the Famine-Genocide of 1932-1933.” The monument has appeared on postage stamps of Ukraine. It has appeared on coinage. Unveiled in 1993, this was the first monument to the Holodomor to be erected in a newly independent Ukraine.

Also in Kyiv, on a hill above the Dnipro River, less that a kilometre downstream from the Pecherska Lavra Monastery, the holiest site in the Eastern Orthodox religion, stands a tall monolith topped by a stylized flame. This is Kyiv’s second Holodomor memorial. Near the monument is an evocative brass statue of a gaunt, plaintive child. A thin, starving child. Barefooted, she clutches a few stalks of wheat. Her hair is braided in two rows, and in her eyes is a look of hopelessness.

#

BioInfo of Author

Gord Yakimow, a first-generation Canadian, is the offspring of a father who immigrated to Canada in 1928, and an Irish mother who came to Canada as a War Bride in 1946. His parents met and married in London, England, while his father was recuperating from wounds suffered during World War II.

His Japanese-sounding surname came courtesy of an immigration officer: when his father arrived in Canada he spoke no English … and this name was “close enough” to the Slavic pronunciation of the Ukrainian name. Not an uncommon story.

He has served as the founding president of Prosvita, Yukon Ukrainian Association, and as president of the Fraser Valley Ukrainian Cultural Society in British Columbia. He has for many years been involved in the organizing of the BC Ukrainian Cultural Festival.

A retired teacher, he lives in the Fraser Valley, about 100 km east of Vancouver.

This article was first published in the Winter 2010 edition of Solovei Magazine (no longer in production). It is reproduced here with permission of the author.

Share on Social Media