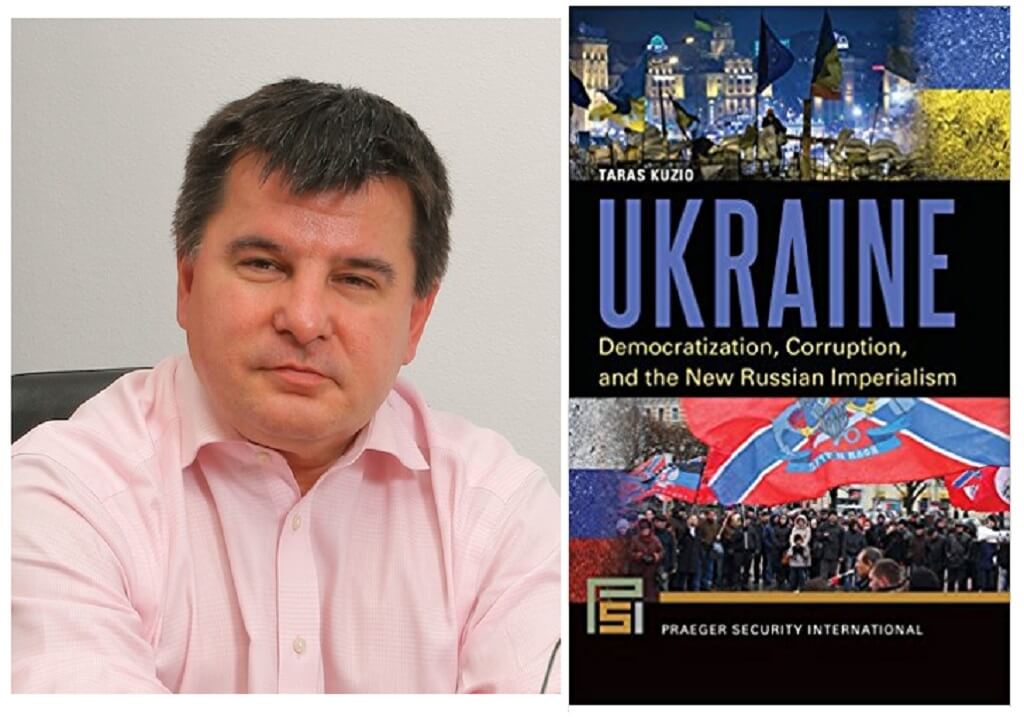

Jaroslaw Wasyluk for NP-UN.

Most recent analytical studies related to contemporary Ukrainian history are set within the context of East-West relations or within the history or geopolitics of the region. Missing so far is a more profound insight into the internal dynamics of contemporary Ukrainian history. Many Western historians unfortunately have little background knowledge to present this kind of history.

In the absence of firm grounding in the history and language of the USSR’s successor states, some political scientists are left to base their information on second-hand sources. Unaccounted are the underlying tenets that motivate today’s Ukrainians. In explaining developments in Ukraine, they depend on English language press reports, missing some crucial parts in the evolving story as in the case of “the ousting of Yanukovych”, when opposition politicians had actually come to an agreement with him on the very day he fled. This puts a different hue on the so called “coup”, which supposedly took place and hints on a well-prepared plan. Reliance on “historical myths” rather than documented facts are also tempting; stereotyping or making quick off-the-cuff assumptions is yet another “trap”. An often-repeated argument is that the conflict in Ukraine is between Ukrainian and Russian speakers or simply Orthodox believers defending their faith and values against NATO and the EU. In Democratization, Corruption, and the New Russian Imperialism, Taras Kuzio dispels these arguments quite successfully through his very good background knowledge and historical approach. He is certainly well placed to show how current events relate to processes Ukraine experienced after the death of Stalin and what problems may arise in contemporary politics. However, his discussion on the relevance of post-war émigré politics in today’s Ukraine may not mean much to the English-speaking reader, ineffective as they were, as Kuzio admits. Also, there is little discussion on how the Chornobyl catastrophe may have changed the mind-set of Ukrainians. Oksana Zabuzhko has remarked that the catastrophe made her feel more Ukrainian than Soviet as a result.

Since 1991, Ukraine has striven for sovereignty and democratic values but so far, these values have borne very shallow roots. Totalitarianism, as Motyl points out, has left a deep-seated legacy impervious to change. The failure to introduce land reform is a good example of how Soviet thinking still prevails in Ukraine. The danger to democratic institutions such as parliament is evident. In the eyes of the average Ukrainian, parliament is being seen more and more as a place of self-enrichment, realisation of personal ambition and corruption than a place where democratic values are enshrined. The idealism that brought about the Orange Revolution or the Revolution of Dignity, is in danger of being dashed when promises given by self-serving politicians are not realised (judicial reform; uncompleted cases against individuals responsible for violent acts against Maidan supporters). Politicians are more prone to conclude back room deals than to follow the law through to the end. Anything has its price and can be bought. Without rooting out corruption in the uppermost echelons of power, real justice or democracy will never prevail elsewhere. It would be really tragic if cynicism overcame constructive ideas in Ukraine. As Kuzio puts it, there is a lack of understanding across the political spectrum in Ukraine of the law as a central component of democracy and the market economy. There is much truth in the statement that Ukrainians are good at conducting revolutions but bad at building a state that caters for all its citizens. One saving grace, however, is that, though civil society might still be in its infancy in Ukraine, its critical voice is getting stronger, and hopefully will strengthen attitudes advocating reform. Where the state has failed to care for its citizens volunteerism has stepped in and has, as Kuzio points out, done a most remarkable job.

One of the main tenets of Kuzio’s book is that national identity is constantly in flux. Western Ukraine has been quite fortunate in her history to develop an exclusive Ukrainian national identity within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But this has been possible to a lesser degree in Transcarpathia and certainly not in Ukrainian lands in the Russian or Soviet empires where the Tsarist and Soviet authorities expressed an “all embracing hostility” to a Ukrainian identity thus conserving the existence of multiple identities.

The author uses the idea of seven competing cycles from 1953 to the present day (both pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian) in order to bring these interrelating historical strands together and to provide a fresh perspective on Ukrainian contemporary history. Each turn of the cycle represents a potential change in Ukraine’s orientation: East or West. But now the events of Maidan in 2014, have completely discredited Yanukovych’s policies, placing Ukraine firmly on the road to Europe, a process which, hopefully, will be irreversible. Kuzio argues that during Kuchma’s rule, in the early 1990s, an equilibrium was achieved in east-west views that was able to satisfy people both in Western and Eastern Ukraine, and that a return to this “centrist” policy is now needed. The question remains: is this possible? Also, will the ruling coalition hold together without major upheavals and not allow itself to be compromised by internal and external hostile forces? The main difference in this turn of the cycle (compared with other cycles) is the war in Donbas which is fomented by Putin and his ideology of Euroasianism. What is important for Ukraine, is reaching the point in the cycle when full Ukrainian integration is possible and successful.

Will the Ukrainian political elites consolidate to work in Ukraine’s interests or will self-interest win the day? There is much evidence to suggest that elite figures, the oligarchs, are still pursuing self-advantageous deals using business and politics as they see fit. They have made little effort to change even during the war. Russian remains the language of the business elites while the English-speaking world remains foreign to them. In effect, as Kuzio writes, they remain provincial in outlook. Trade with Russia precludes any need for modernisation or industrial reform. Oligarchs control monopolies as they have done in the past denying any healthy competition in industry to develop. However, Acemoglu and Robinson state that in countries where rich elites are disinclined to share profits with the rest of the population the end result could be a failed state.

Kuzio’s use of historical cycles brings clarity and a sense of perspective into the narrative. Can one detect any change of attitudes amongst the people today? Radio Svoboda has recently reported that in 2017 92% of citizens of Ukraine (not including those under occupation) identify themselves as Ukrainians by nationality as opposed to 2015 when the figure stood at 86%. Also, Eurointegration is now a more acceptable concept in wider Ukraine. The Maidan revolution of dignity has galvanised attitudes amongst Ukrainians in favour of a more common national stance. Putin’s plan for the creation of Novorossiya has failed, and the process of decommunization has made headway. However, the government still fails in its obligations to eastern Ukrainians. So, the question remains – will the day that Ukrainians identify with common national interests come sooner than later? Kuzio remains optimistic in this regard.

Taras Kuzio’s volume is very rich in detail and this reader believes that some abridgement of content might be necessary. But all in all, this is the only existing work to present Ukrainian contemporary history as it is evolving today.

Share on Social Media