Emily Bayrachny.

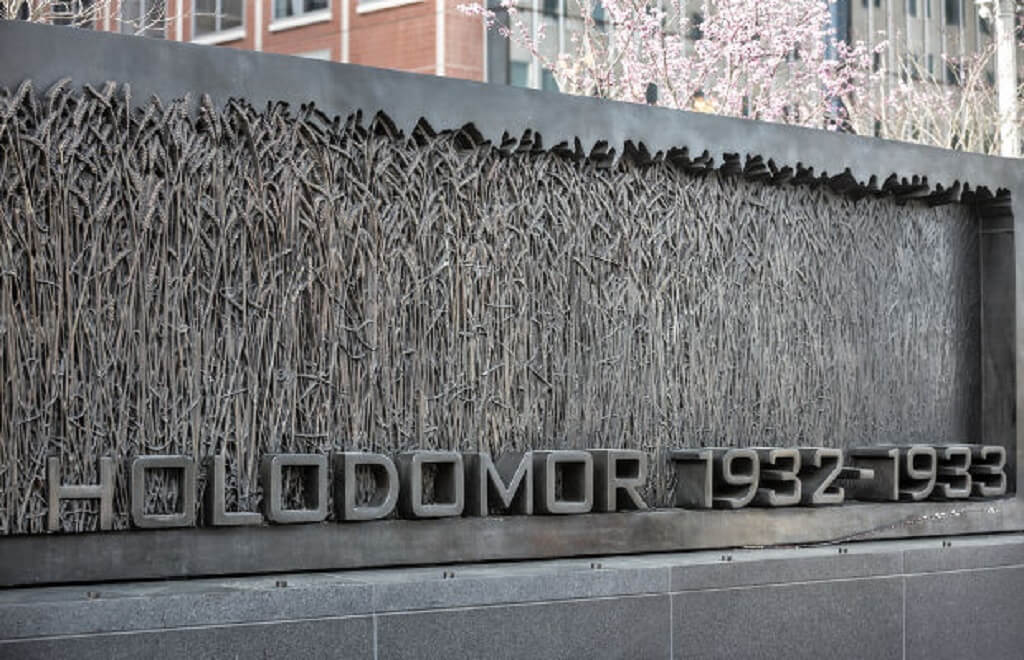

This year marks the 85th anniversary of the Holodomor, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s genocide of the Ukrainian people by means of organized mass starvation. As in previous years, the fourth Saturday of November is commemorated around the world as Holodomor Memorial Day. As a descendent of Holodomor survivors, this genocide haunts me to this current day. The effects of this artificial famine, however, are not only felt by its survivors – it affects all of us fundamentally as Canadians who firmly value and champion human rights. The current global climate carries ominous echoes of the 1930s, with the rise of nativism, a disregard for international human rights and a growing complacency to autocratic regimes murdering their people.

I look at today’s world 85 years after the Holodomor, and I am afraid. We are seeing an increase of authoritarian rule around the globe. The appalling treatment of the Rohingya by the military regime in Myanmar has been met largely with indifference by the world. Vladimir Putin’s abuse of Crimean Tatars and other ethnic minorities in the illegally occupied Crimea continues to this day, despite condemnation from the international community, including mechanisms such as sanctions. The world failed to respond quickly enough to the deliberate murder and torture of thousands of Yazidi women and girls at the hands of Daesh. Mass murder and routine abuses of human rights are becoming increasingly apparent in the world, with the exception of a few lone voices who speak out against the growing darkness.

Genocide is a process; it has a beginning, mid point and end. Mass murder in the millions does not occur overnight; regimes systematically escalate their attacks against targeted groups when there is a lack of opposition and the international community is indifferent. For instance, the attack against ethnic Ukrainians in the Soviet Union was first marked by an assault on the Ukrainian language, reversing the “Ukrainianization policy of the 1920’s which sought to promote it and the demonization of Ukrainian peasants as “kulaks” or rich farmers, which quickly escalated to mass executions of Ukrainian Orthodox clergy, intellectual and political leaders. The Soviet regime sank to its lowest depths when authorities confiscated all food, sealed the Ukrainian border and executed anyone suspected of harbouring anything remotely edible.

The Holodomor was fundamentally rooted in xenophobia, as were many of the genocides carried out against ethnic minorities by Stalin’s murderous regime. In the case of Soviet Ukraine, the assault on the Ukrainian language, the mass killings of clergy and the intellectual elite finally led to the extermination of millions of Ukrainians through organized famine.

Genocides like the Holodomor are successful when others turn a blind eye to human suffering and the abuses of autocrats. Few countries condemned the Holodomor in 1933 for what it was: a genocide of horrific proportions aimed at exterminating the Ukrainians as a nation. None were willing to stop the murderous course of action Stalin carried out. Today, many countries, Canada among them, have rightfully recognized the Holodomor as genocide. Too many still deny the facts.

When we look back at events like the Holodomor, survivors mourn and humanity collectively swears “never again.” Our indifference to the crimes taking place today and to the risks of future atrocities underscores our complicity. Now more than ever, racism and state discrimination against minorities need to be addressed and swiftly condemned. We must identify genocide wherever it occurs, protect the victims and bring the perpetrators to justice. Genocide must be recognized for what it is: humanity’s darkest act. Without global vigilance and a keen concern for the wellbeing of vulnerable groups around the world, horrors like the Holodomor are doomed to be repeated.

This article was prepared under the auspices of the UCC Journalism Mentoring Project

Emily Bayrachny is a policy analyst with expertise on Ukraine and the former Soviet Union. She holds a Master of Science in International Relations from the London School of Economics. Her dissertation on the war in Ukraine entitled “Church, State and Holy War: Assessing the Role of Religious Organizations in the War in Ukraine” was recently published. A descendent of Holodomor survivors and member of the Ukrainian-Canadian community, she lives in Ottawa.

Share on Social Media