Ganna Zakharova, MA, MSW, RSW for New Pathway – Ukrainian News.

Since childhood I absorbed the inevitable family truth that bread is Holy. You can never throw it away, and you always must finish your meal, even if you are full. This belief is a national indisputable truth that is being passed from generation to generation among Ukrainians. This statement sounds like beautiful wisdom. However, the origins of this wisdom are unfortunately sad. This teaching stems from a collective fear of starvation caused by the Holodomor genocide in Soviet Ukraine in 1932-33 and which still affects Ukrainians around the world.

This past week Ukrainians around the world honored the victims of the Holodomor genocide. On International Holodomor Memorial Day, which this year falls on November 27, Ukrainian communities across Canada lit candles and said prayers in memory of their perished family members.

Death by hunger

Holodomor (to kill by starvation) was a famine orchestrated by the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin Communist rule in 1932-33. Holodomor took 8 to 10 million of lives of ethnic Ukrainians; yet, it has been silenced and denied at all times. Only after the Soviet Union collapsed, Soviet KGB archives in Ukraine about Holodomor became declassified. The “Terror Famine” was an act of revenge and suppression of the Ukrainian farmers who rebelled against the Soviet collectivization – the forced collection of farmers’ and villagers’ crops and kettle to the state collective farms. While two other famines in 1921-22 and 1946-47 might be explained by drought, crop failures and the war; the harvest in 1932 was very good. There were no natural causes for the famine. In addition to crops and cattle, the armed Soviet special units took all food and household items including pickles, domestic animals, clothes, shoes, and even blankets and pillows. The collectors even used long metal poles to probe the ground looking for buried food. The borders were closed, so nobody could escape from the death trap.

They are among us

The Holodomor is not something Canadians know much about, even though, Ukrainians are Canada’s eleventh largest ethnic group. One-quarter of the entire population of Soviet Ukraine perished at that time, and many Holodomor survivors reside here in Canada. I was surprised to find out that my university classmate, Anna Chpilevaia, is also a descendant of Holodomor survivors. She was the only one in the class who knew about it, because her own great-grandparents died from hunger during the Holodomor. Larysa Faulkner, the Coordinator of Research Funding and Facilitation at the Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, also comes from a family of Holodomor survivors. Her grandparents survived the Holodomor and told her parents a lot of stories about those times.

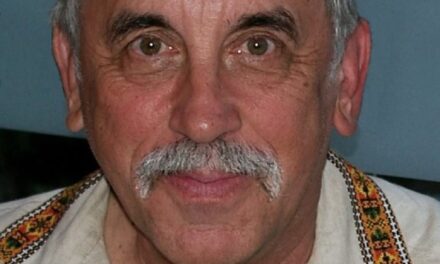

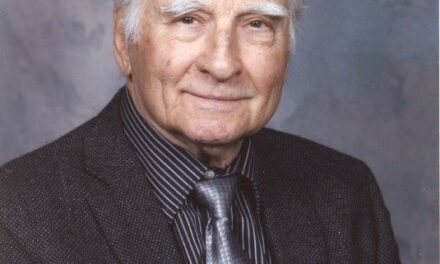

I had the privilege of interviewing Ms. Faulkner’s parents Nina and Ivan Chumak about their family story and the Holodomor. Most of the stories came from Nina’s mother, Anastasiia Koshel, who was a third-grader during this famine. Nina and Ivan Chumak immigrated to Canada just a couple of years ago. All their life they lived in Khrystynivka, Cherkasy region, central Ukraine. All of their ancestors lived in that village.

Horror stories part of oral history

Anastasiia told her daughter Nina horror stories of the weekly wagon that came each week collecting dead swollen bodies and some that were still alive, but barely breathing. All of them were transported to a pit for collective burial. Many children were orphaned or went missing. Anastasiia’s little sister was coerced by the neighbor into her house. The woman promised to treat the girl with cooked mushrooms. Instead, the girl got a piece of plain flat bread made from weed seeds and potato pills. As she was eating the treat, she heard the neighbor sharpening a knife. She quickly understood the neighbor’s evil plan and fled. Anastasiia’s little sister managed to escape and stayed alive; millions of others weren’t so lucky. Those who did not starve to death and resisted Soviet rule were executed on the spot or sent to Siberian concentration camps. This included intelligentsia, political leaders, writers, artists, clergy, and farmers.

Collective intergenerational trauma

“I thought I would never have enough bread,” Anastasiia Koshel quietly shared with her daughter Nina. Anastasiia spent her life collecting bread crumbs, and never threw food away. She passed away in her 50s.

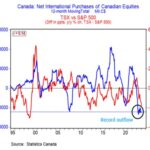

Despite the efforts by Kremlin propaganda to deny the Holodomor, the genocide continues to be researched from different perspectives. More emerging research also focuses on psychosocial consequences of the Holodomor and how intergenerational trauma manifests itself. In 2015 Brent Bezo and Stefania Maggi conducted research of three generations in 15 Ukrainian families and published an article “Living in “survival mode:” Intergenerational transmission of trauma from the Holodomor genocide of 1932-1933 in Ukraine.” The article provides interesting data on how the silenced Holodomor has taken a toll on the next generations individually and socially. Living in fear, having anxiety, stockpiling food, being afraid to speak up, low self-esteem, suppressed anger and addictions, as well as high levels of mistrust of the authorities, dismay with the government and corruption are just a few consequences of the silenced genocide of Ukrainians. My own grandfather lived through the Holodomor as a child and through other atrocities during Soviet times. He, like many others in his native region, developed an alcohol addiction. A habit of stockpiling canned food in the cellar is part of my family culture too.

The essential part of healing a collective trauma is talking about it, revealing stories of survivors and commemorating the victims. Multiple resources are available to learn more about the Holodomor. The Ukrainian World Congress has launched the Holodomor Descendants Network that serves as a platform for collecting personal stories of Holodomor survivors and their families. The Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre and the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium (HREC) provide a collection of research articles, documents, textual and photo records, narratives and films, including declassified Soviet KGB files such as Nikolai Bokan’s photos and diaries. In Ukraine, the National Museum of Holodomor-Genocide has been created to continue research and uncover the truth that has been silenced for decades.

In Canada the Holodomor genocide was officially recognized in 2008 with the Ukrainian Famine and Genocide Holodomor Memorial Day Act. Since then, the fourth Saturday of November is Holodomor Memorial Day. Holodomor has been recognized as a genocide by the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Quebec. Around the world the Holodomor genocide of Ukrainians has been recognized by 17 countries.

Share on Social Media