NP-UN National Affairs Desk.

While most Canadians are aware of the existence of unmarked graves at former Residential School sites, few know that similar burial sites can be found by the internment camps in which Ukrainians were imprisoned during World War I, says a leading expert on that chapter of Canadian history.

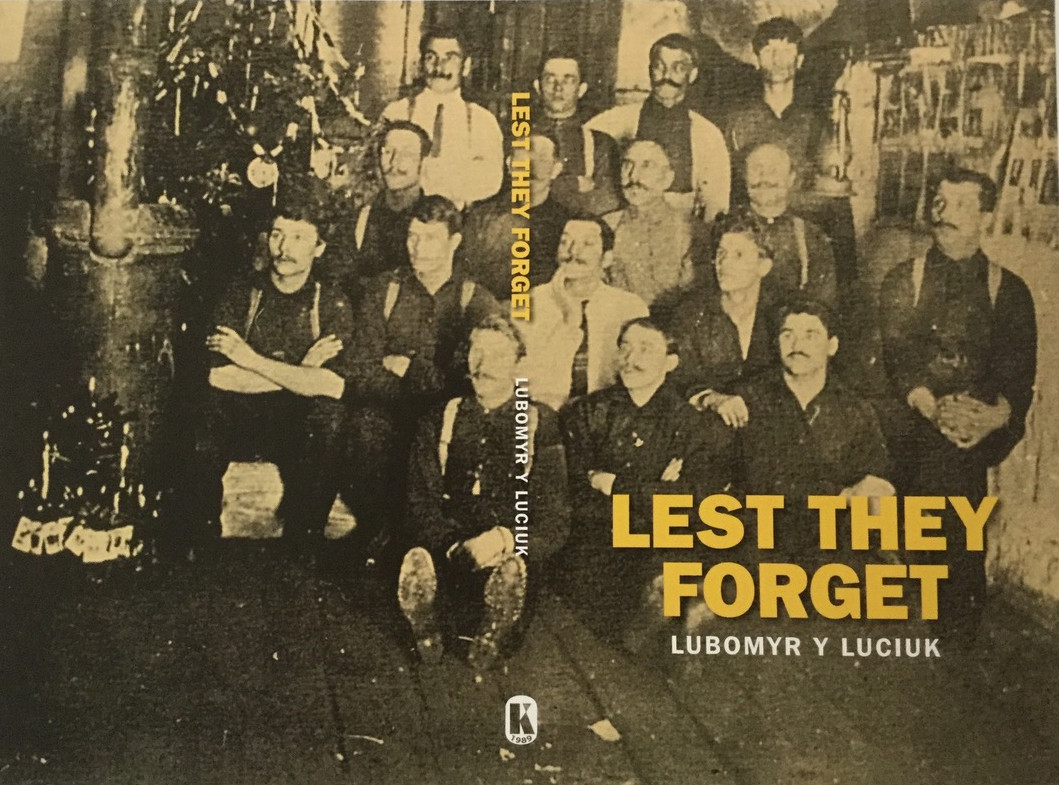

“There are Ukrainians still buried in the boreal forest. If you want to talk about unmarked graves in rural areas that no one knows about, we have our own,” said Dr. Lubomyr Luciuk during the launch of his book Lest They Forget, co-sponsored by the Ukrainian Canadian Professional and Business Association of Edmonton and the League of Ukrainian Canadians at the Ukrainian Youth Unity Complex in Edmonton, April 28.

The book is compilation of published opinion-editorials on the subject of redress for Canada’s first national internment operations of 1914-1920, most written between 1988 and 2022 by the author/compiler. These are complimented with archival materials and photographs about the redress campaign organized by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association and its supporters, resulting in the creation (8 May 2008) of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

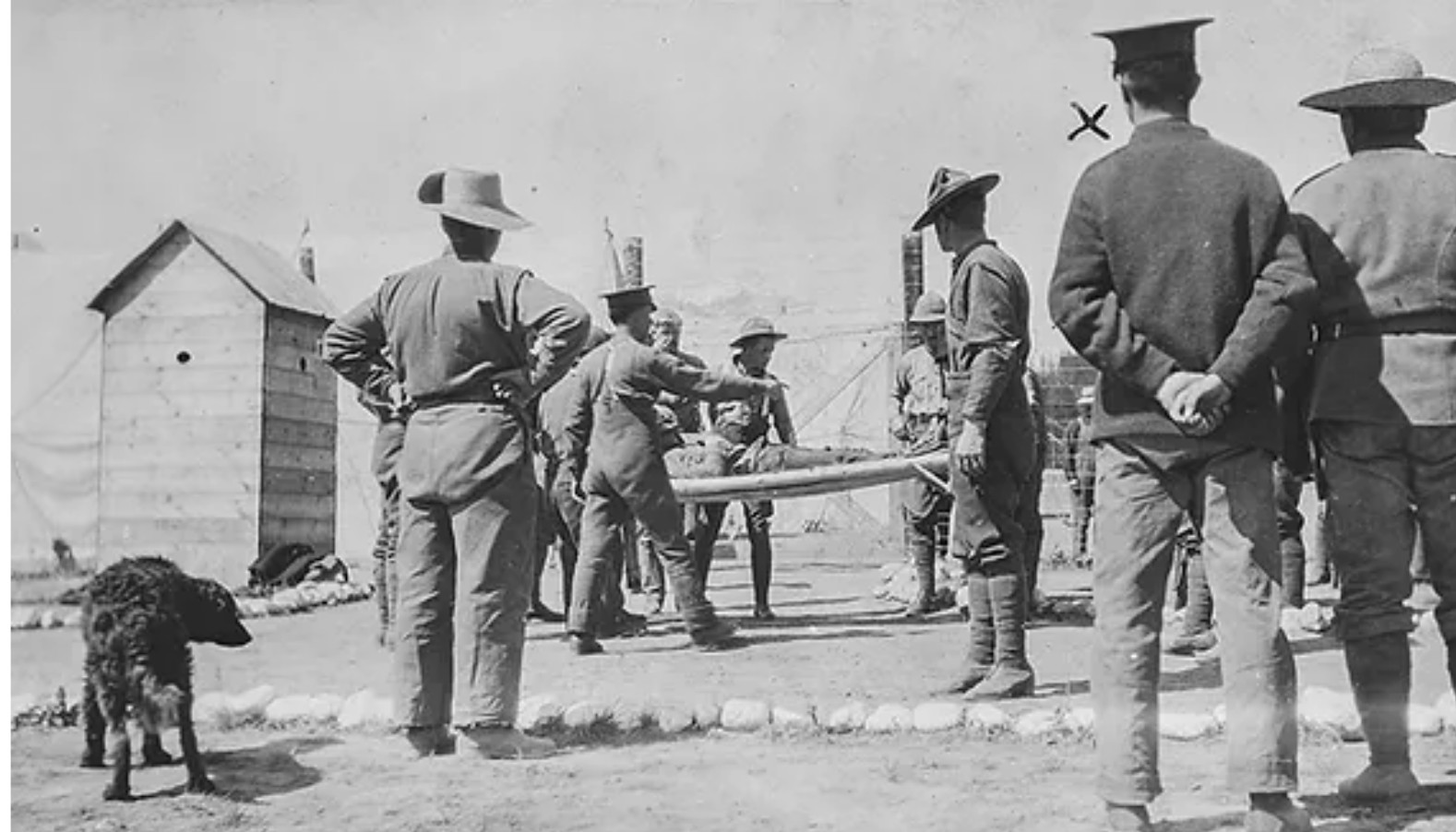

These operations saw members of Ukrainian families separated and their property confiscated and sold. Thousands of Ukrainian men were consigned to internment camps and years of forced labour in Canada’s wilderness. Some have argued that the infrastructure development programs that received “free” Ukrainian labour benefitted the Canadian government and the captains of industry to such an extent that the internment continued for two years after the First World War had ended.

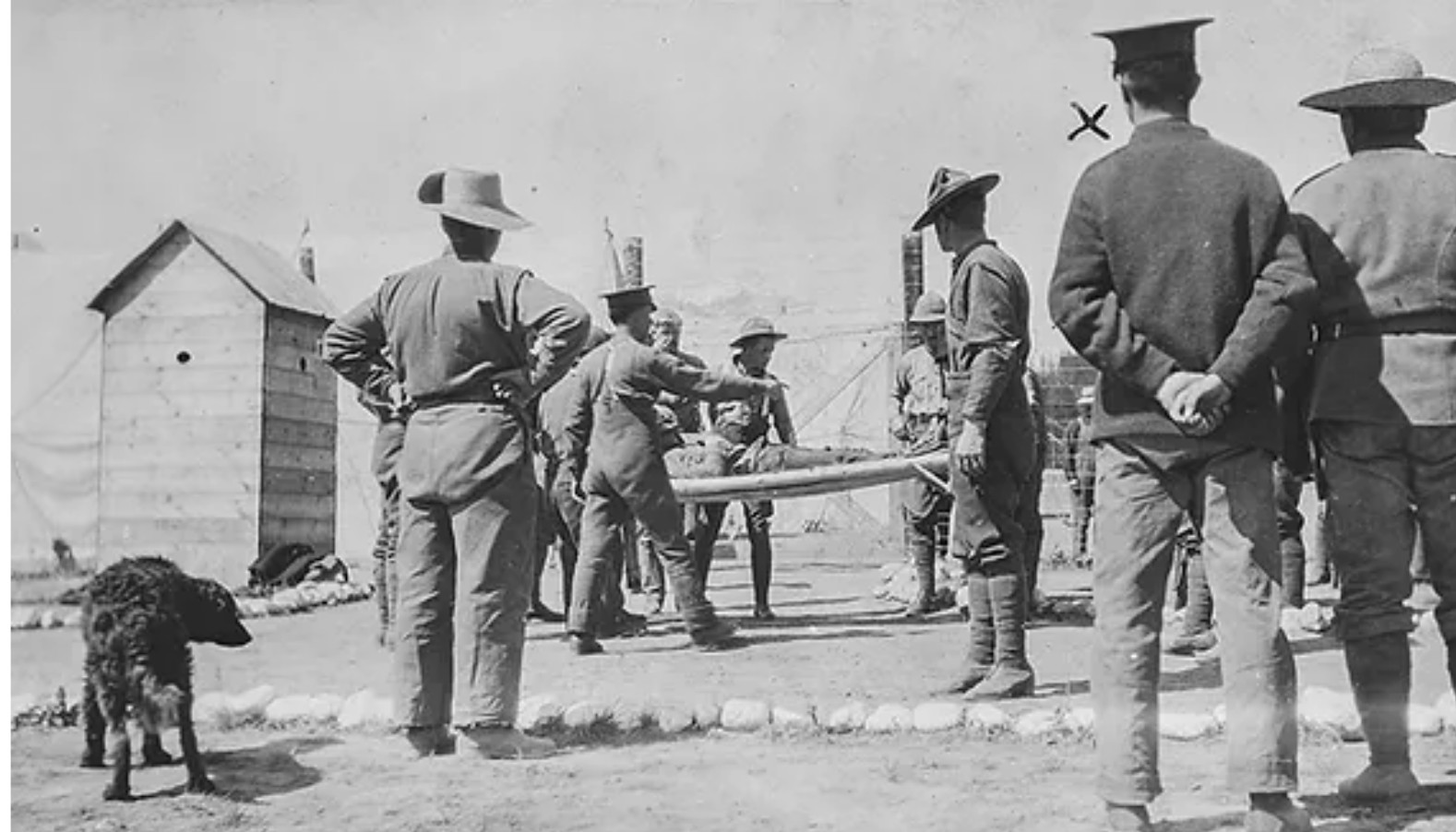

Shooting of a prisoner at the Castle Mountain Internment Camp. Here he is seen being carried away on a stretcher to the prisoners’ hospital where he recovered. August 1916. Provincial Archives of Alberta. A15289.

The Government of Canada considered Ukrainians to be “enemy aliens” as most of them came from what was then Austria-Hungary with whom Canada was at war.

About 80,000 Ukrainians had to register as “enemy aliens” and 8,579 males and some women and children, most of whom were Ukrainians were interned by the Canadian Government,

They proceed with this policy despite British instruction not to do so because they considered “friendly aliens”.

Luciuk attributed the Canadian government’s decision to the inherent racism displayed towards the Ukrainian settlers by the population at large.

As an example, he cited an 1899 letter to the editor of the Calgary Herald by Rev. Father Moris who stated the following:

“As for the Galicians [Ukrainians] I have not met a single person in the whole of the North West who is sympathetic towards them. They are, from the point of view of civilization, 10 times lower than the Indians. They have not the least idea of sanitation. In their personal habits and acts, resemble animals, and even in the streets of Edmonton, when they come to market, men, women, and children, would if unchecked, turn the place into a common sewer”.

This episode in Canadian history has been largely overlooked by historians, but a concerted effort by the Ukrainian community to have it recognized resulted in the establishment of the $10 million Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund under the Conservative administration of Steven Harper. This fund uses the interest earned on that amount to fund projects that commemorate the experience of thousands of Ukrainians and other Europeans interned between 1914–20 and the many others who suffered a suspension of their civil liberties and freedoms. The funds are held in trust by the Ukrainian Canadian Foundation of Taras Shevchenko.

Today the history of the internment operations is taught in every province.

The agreement was negotiated for the community by Paul Grod, President of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress; Adrew Hladyshevsky, President of the Shevchenko Foundation and Luciuk on behalf of the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

Luciuk said that records of the internment were destroyed, but Edmonton historian Peter Melnycky discovered a document that stated this was done because the government claimed they had “no evidentiary value”. We also know that money was left in the coffers of government, about $29,000 in the currency of that time. But by extending it to 1991 with compound interest and taking the value of the forced labour, the internationally recognized accounting firm Price Waterhouse established the loss at $30 million. “This was a significant economic blow and exploitation of the community.”

But as Mary Manko, the last known survivor, who was six-and-a-half when she was sent to the Spirit Lake internment camp where her sister died, told Luciuk:

“This is not about money. This is about memory.”

Note: Lest They Forget is available in public and university libraries across North America.

Share on Social Media