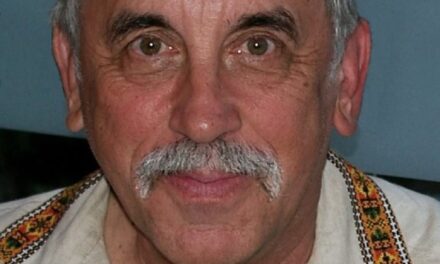

Gord Yakimow for New Pathway – Ukrainian News.

It was the third day of my tour of various sites associated with the D-Day (June 6, 1944) landings in Normandy when, seeing a particular name on a grave in the Canadian Beny-sur-Mer cemetery near Caen, I was deeply moved:

W Rohatynski #H41254; Served as W Ratynsky; Royal Winnipeg Rifles; 4th July 1944 Age 25; In fond memory; Of our son and brother; Rest in Peace; Mother, Dad and Family.

I was on the trail of my father’s battalion in the days after D-Day. He had landed at Juno Beach on approximately D+30 (i.e. 30 days after D-Day) with the Royal Canadian Engineers. His unit moved inland, rebuilding an airport, badly damaged by allied artillery fire and by retreating Germans, and then building a Bailey bridge, both near Caen in Normandy, France. Then they moved on northward through Belgium and Holland and finally into Germany as the allied front advanced.

I’d been visiting places associated with D-Day for the first two days of my tour – museums, monuments, battlefields, and cemeteries. Many cemeteries … with their thousands of identical headstones. Many inscribed with “Unknown Soldier.”

Cemetery in Beny-sur-Mer

My father, John Yakimow, was an immigrant/refugee from Galycia (Halychyna) in Western Ukraine. As a teenager, he had fought with the Ukrainian Sich Sharpshotters (Ukrainski Sichovi Stril’tsi) in the days following the confusion of the Russian Revolution when a small window of opportunity opened up for Ukrainian Independence. That independence (1918-1922) turned out to be short-lived.

He arrived in Canada in 1928 — part of the “second wave” of Ukrainian immigrants, and missed the Holodomor by just a few years. When he enlisted in the Canadian army in 1940, he lied about his age, for he was older than the cut-off age for volunteers. His medical certificate was “doctored” by his doctor.

“Your father was definitely here,” asserted my guide, Jim Smithson. “Although not part of the D-Day Invasion, the Royal Canadian Engineers played a vital back-up role. As they were rebuilding Carpiquet Caen Aeroport, they were close enough to the front lines to see and hear the artillery.” [At some point, John Yakimow was wounded by shrapnel from a German bomber, and he was sent to London to heal.]

My father’s name underwent several manifestations in his early years in Canada: Jakymow, Jakymiw, Yakymow, Yakimow, Yakymiw. Names provided by Canadian Immigration personnel. The final one was closest to the Ukrainian phonetic pronunciation.

When John Yakimow sent packages from Canada to his family in Soviet Ukraine, they were addressed to his family in Selo Cherniw, Pochta Rohatyn (village of Cherniw / Post Office in Rohatyn). So I thought it likely that W Rohatynski’s people were from Rohatyn, and whether his nomenclatural experience was similar to that of my father: an immigration officer ascribing a name based on information provided and misunderstood. Not an uncommon occurrence in those days.

Thereafter, as I walked the rows in the cemeteries we visited, I looked in particular for what appeared to be Ukrainian names. And there were many. I photographed a few.

The Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery at Reviers, Normandy, near Caen, is a relatively small cemetery in comparison to others – it contains only 2,048 graves. Here lie the remains of W Rohatynsky. Here also are the graves of the following Ukrainian-Canadian soldiers:

C Huzyk (#H102547 – age 22), Regina Rifle Regiment, “Dear Son of M and A Huzyk, Winnipeg;

G Kindrachuk (B112654 – age 25), Regina Rifle Regiment, “Dear son of Paraska Kindrachuk, Hafford, Saskatchewan;

SR Chermishnuk (#L12710 – age 26) South Saskatchewan Regiment.

Like most of the war cemeteries, Beny-sur-Mer contains many graves marked “Unknown Soldier.”

A nearby cemetery near Cintheaux, Normandy, the Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery, contains 2,958 burials of which 89 are “unknown soldiers.” Here lie the following soldiers killed in battle:

R Gorodetsky (#D83173), Black Watch Royal Highland Regiment;

P Wasyluk (#147144), Lincoln and Welland Regiment;

M Michaluk (#M100370 – age 22), Canadian Scottish Regiment;

P Evanchuk (#H7018 – age 27), Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, “In loving memory of Peter, Born Winnipeg, Manitoba”;

M Mandzuk (#H10124 – age 23), Royal Regiment of Canada, “Beloved only son of George & Mary Mandzuk, Whitemouth, Manitoba”).

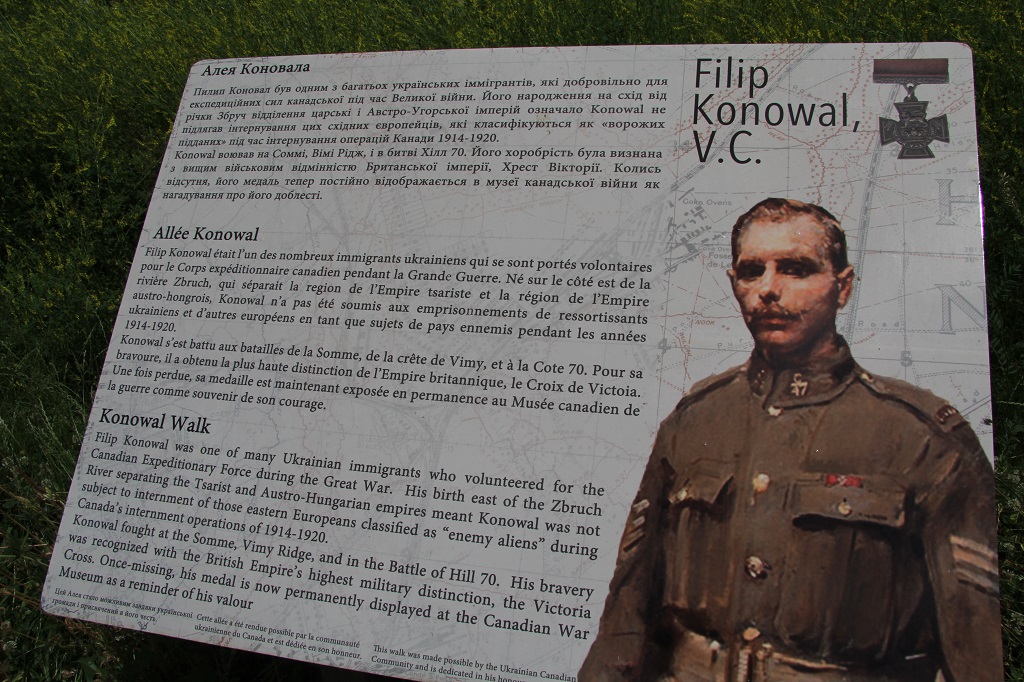

The Canadian Memorial on Vimy Ridge near Arras has on it the names of 11,000 Canadians whose remains lie somewhere in the fields of Flanders or the Somme or the Ypres Salient – either in a grave marked “An Unknown Soldier from the Great War,” or somewhere still beneath the dirt and clay of what was once the Western Front.

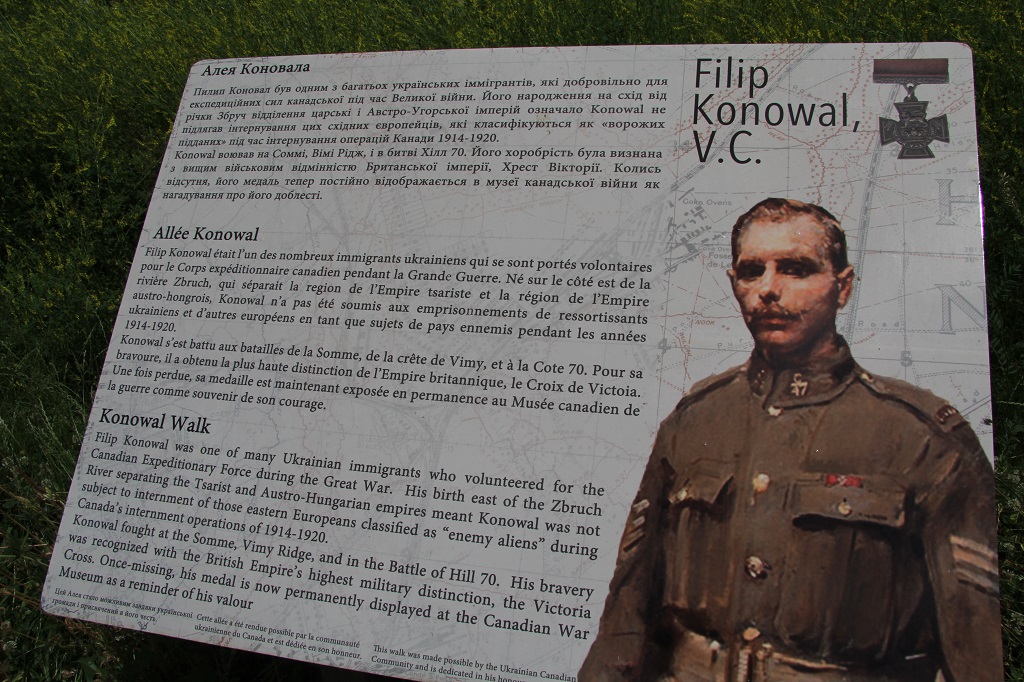

Nearby is “Hill 70,” where Filip Konowal displayed such fearlessness and bravery while in battle that he was awarded the highest honour that can bestowed upon a soldier from a Commonwealth country, the Victoria Cross. Konowal is the only Ukrainian-born Canadian to have received the VC.

Fifty kilometres to the south is the Thiepval Memorial. It is to Great Britain what the Vimy Memorial is to Canada. What is poignant about Thiepval is that the memorial at the site has inscribed onto it 72,000 names – young men killed in the Somme, most between July and November of 1916 … their remains never identified.

Fifty kilometres to the south is the Thiepval Memorial. It is to Great Britain what the Vimy Memorial is to Canada. What is poignant about Thiepval is that the memorial at the site has inscribed onto it 72,000 names – young men killed in the Somme, most between July and November of 1916 … their remains never identified.

On the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium, there are inscribed the names of 54,000 soldiers – killed in the fields of Flanders, but whose remains were never identified. I scoured the walls to locate names which appeared “Ukrainian-ish.” If these soldiers were indeed Ukrainian and from Canada, they would have avoided interment as “Enemy Aliens” because they had hailed from a region in Ukraine which was not at the time controlled by Austro-Hungary.

There were relatively fewer such names than I had spotted in the WWII cemeteries of Normandy … but there were a few: GF Nikitichen, J Ogorodnik, CE Spytko, S Hachey, L Radokovich, G Kolesar.

All that remains of the Bailey bridge that my father and his battalion of the Royal Canadian Engineers had been involved in building over the River Orme near Caen is a cement footing, from which extends upward a rusting steel piling. I crawled through bush to locate it. On each of the four flat surfaces of the footing a soldier had imprinted his name and serial number into the concrete. Young men who had served with my father. One was perhaps Ukrainian: W Kwiozak (#K50640) RCE 29/8/44. Eighty-four days after D-Day.

Although wounded by shrapnel, my father survived the war. I was one of the “post-war baby-boomers.” As a child I can recall him yelling out in the night, my mother trying to calm him from yet another bad dream. Not all war wounds were physical.

Gord Yakimow is a retired teacher, having had stints in Manitoba, Ontario, Great Britain, the Yukon Territory, and British Columbia. He now lives in the Fraser Valley, about an hour east of Vancouver. His articles (and photos) have appeared in a variety of publications, including PostScript (for BC teachers), UpHere (from Yellowknife, NWT), The Outdoor Edge (outdoor activities), Solovei Magazine (Ukrainian issues in Canada), the Ukrainian News (Edmonton & Toronto), and in several BC Black Press newspapers. He has been a long-time member of the organizing committee for the annual BC Ukrainian Cultural Festival.

Share on Social Media