By: Rachel Caklos

The Holodomor, “The Hidden Holocaust,” was a horrific genocide of “murder by hunger,” a large-scale famine inflicted upon Ukraine between 1932 and 1933, engineered by the Stalin regime. The death of eyewitnesses and a fear campaign were waged against the Ukrainian people silencing whole generations. Today, we continue to unearth more information on the impact of the famine, alongside the scale of the famine’s denial. Much of the discovery of the Holodomor has been and continues to be driven by scholars and survivors who recount their stories to their families, friends and the world, leading to its preservation and recognition today.

This article focuses on exploring the importance of oral history and how it has enabled the preservation and increased awareness of the famine. I have included personal interviews where survivors divulged their painful recounting of stories and explained why it took so many years to speak up about this horrendous tragedy. Zina Mayewsky, a victim of the Holodomor, has kindly shared her account of suffering as a child in a village in Ukraine. A primary account that she shares as evidence of her life during the Holodomor.

Importance of Oral History

Alessandro Portelli, an oral historian, emphasized the importance of oral history, creating a profound understanding of the true event that unfolded and the feeling of experiencing it first-hand:

“The first thing that makes oral history different, is that it tells us less about the events and more about their meaning. The unique and precious element which oral sources force upon the historian, which no other sources possess in equal measure, is the speaker's subjectivity.” (Mckenna, 2003)

Since Stalin’s government actively denied that the Holodomor was planned, the oral sources from the people of Ukraine were pivotal in providing the evidence that kept this catastrophe from being erased from history. The difficulty of oral history is that it is considered ‘objective’ and lacks validity due to bias, distortion and ambiguity.

The Holodomor Reader, compiled and edited by Bohdan Klid and Alexander J.Motyl, discloses oral interviews of survivors and eyewitnesses of the famine. These testimonies allow readers to understand and follow the detailing of events, evidencing the importance of oral history in helping to unravel the Holodomor.

A survivor, the wife of Ivan Zhuk, went to Winnipeg from Ukraine to escape and recount her experiences to the public, exposing the famine. She was brought to the editorial office of The Ukrainian Voice where she participated in an interview on September 13, 1933. The broadcasters describe her appearance, “she wore what looked to be poor clothing and looked like she was from another world.” (Klid, Bohdan & Alexander J. Motyl., 2012) As they conducted the interview, she described the dreadful events that were unfolding in Ukraine:

Q: When did you leave home?

A: On August 5.

Q: How were people living in Ukraine at that time?

A: There was a terrible famine. People were dying of hunger like flies.

Q: Did many die of hunger?

A: As far as I could learn, 25 versts [ca. 17 miles] in either direction about one-quarter of the population survived. Three-quarters died.

Q: Are people suffering the famine quietly, or are they rebelling?

A: How are they to rebel, and what will they achieve by rebelling? They suffer because they have lost all hope. They walk like the blind, and they fall wherever death strikes them. No one pays attention to the corpses lying on the streets. People either step over or 2 sidestep them and keep on walking. From time to time they are collected and buried in common pits. Seventy and more people are buried together.

Q: Have you heard anything about instances of cannibalism?

A: Why not? It happens all the time. There have been cases of a mother starving with her children and then killing and eating them when she sees that they are about to die. Or you are walking along the street and you see a corpse. You look around to see whether anyone is watching, and you cut off a piece of flesh and then bake or cook it.

Q: What is the reason for the famine? Has there been a drought or a bad harvest, or are you not sowing anything?

A: There has been a harvest, we sow and we plant, but as soon as anything grows, they take it all away and pack it off to Moscow…

– Klid, Bohdan, and Alexander J. Motyl. Excerpts, pp. 1, 5. Translated by Alexander J. Motyl.

The surfacing of victim testimonies and eyewitness accounts has been vital in the exposure of the famine. Malcolm Muggeridge, a British Journalist, secretly investigated the catastrophic actions against the Ukrainian people without the permission of the Soviets. By sending his findings back home to Manchester in a diplomat’s bag, he was able to avoid communist censorship. His reports illustrated the conditions faced by the Ukrainian people at the hands of the Soviets:

On a recent visit to the Northern Caucasus and the Ukraine, I saw something of the battle that is going on between the government and the peasants…On the one side, millions of starving peasants, their bodies often swollen from lack of food; on the other, soldier members of the GPU carrying out the instructions of the dictatorship of the proletariat. They had gone over the country like a swarm of locusts and taken away everything edible; they had shot or exiled thousands of peasants, sometimes whole villages; they had reduced some of the most fertile land in the world to a melancholy desert. (Perloff, James)

The History of the Holodomor

The Ukrainian word “Holodomor” comes from two words: “holod” means hunger, and “mor” means to exterminate or eliminate. This term also simply translates to “murder by hunger.”

Known as the “breadbasket” of Europe, Ukraine was relied upon by its neighbours for their substantial exporting of wheat and grain. That was until Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union, came to power. Joseph Stalin's life spanned from 1879 to 1953 and was a well-known fierce dictator for thirty years between the mid-1920s until his death. Throughout Soviet Ukraine, it is estimated between six to eight million people perished directly as a result of the famine. Three to five million of these deaths were concentrated between Ukraine and the Northern Kuban region of Russia, largely populated by Ukrainian agricultural workers. The Kuban region was the “ethnographic Ukrainian territory in the southern Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic.” (Romanyshyn, Oleh, et al., 2014, pg.31)

Stalin’s Motives & Impact

The Holodomor developed gradually as a result of the economic and political issues “prompted by the Bolsheviks desire to modernize at unprecedented speed, as well as the determination to break the back of the independent peasantry throughout the USSR in the process.” (Stalin’s Genocides, pg. 71) The Bolshevik Party was a radical faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, later becoming the Russian Communist Party in 1918 under Lenin’s leadership. (Romanyshyn, Oleh, et al., 2014, pg.2) After Lenin passed away, Stalin succeeded in 1924, in 1928, Stalin and Russian leaders started a campaign of forced industrialization. To pay for this modernization, Stalin collectivized the peasantry and took complete control over the grain harvest. Collectivization was the “policy of forcing all farmers to abandon private farming, and to pool all their land and other resources into a collective.” (Romanyshyn, Oleh, et al., 2014, pg 2)

In 1931, the start of the state collection began when the authorities took sizable amounts of wheat away from many Ukrainian regions and the northern Caucasus. Roughly 45% of the harvested wheat was seized, leaving the civilians with very little supply. Any collective farmer who had grain was forced to give it up to the authorities, leaving nothing left to plant or eat for themselves. There were Ukrainian peasant uprisings against the authorities for their policies, tactics and treatment, but the Bolsheviks considered them as “inherently counter-revolutionary and hopelessly backwards.” (Stalin’s Genocides, pg.72) Stalin demanded that all of the grain be collected from the peasants “at all costs” even though local officials protested:

Despite a communist push for collectivization, Ukraine's farms had mostly remained private- the foundation of their success. But in 1929, the Central Committee of the Soviet Union's Communist Party decided to embark on a program of total collectivization. Private farms were to be completely replaced by collectives – in Ukraine known as kolkhozes. This was, of course, consistent with Marxist ideology: the Communist Manifesto had called for abolition of private property. (Perloff, James)

Hunger and desperation struck the Ukrainian countryside and northern Kuban region. In 1932, Stalin demanded Ukraine to increase their grain harvest output by 44%. This goal was considered absurd, and there was no possible way for this to be achieved. That year, none of the villages were able to produce the increased amount of grain required. This failure led to one of the cruellest orders in Stalin’s career: all of the grain was to be confiscated. Authorities seized all of the food from every household. If one did not turn in all of their grain, they were considered to be hoarding state property:

Every brigade had a so-called “specialist” for searching out grain. He was equipped with a long iron crowbar with which he probed for hidden grain. The brigade went from house to house. At first they entered homes and asked, “How much grain have you got for the government?” “I haven't any. If you don't believe me search for yourselves,” was the usual laconic answer. And so the “search” began. They searched in the house, in the attic, shed, pantry and the cellar. Then they went outside and searched the barn, pig pen, granary and the straw pile. They measured the oven and calculated if it was large enough to hold hidden grain behind the brickwork. They broke beams in the attic, pounded on the floor of the house, trampled the whole yard and garden. If they found a suspicious-looking spot, in went the crow-bar. (Perloff, James)

Stalin was angered by the kolkhozniki, the collective farmers, as some vanished across the European regions in search of food. It was thought that tens of thousands of people escaped before peasant emigration was forbidden, however, many were unsuccessful in their attempts.

In February 1933, OGPU troops also known as the KGB (the Soviet secret police that controlled jails and camps) arrested roughly 220,000 people, and from this, 190,000 were sent back home. Others were sent to the Gulag, the Soviet forced labour camp – for many, this was a death sentence. Moscow's approach to achieving its aim of dismantling Ukraine was very methodical. Firstly, they took out all the elites serving in national, cultural, and political fields. Then began closing down the national churches, followed by large-scale executions and mass deportations of people deemed as “enemies and threats to the people.” Finally, the rural population was exterminated by the famine, disassembling the entire nation at its core.

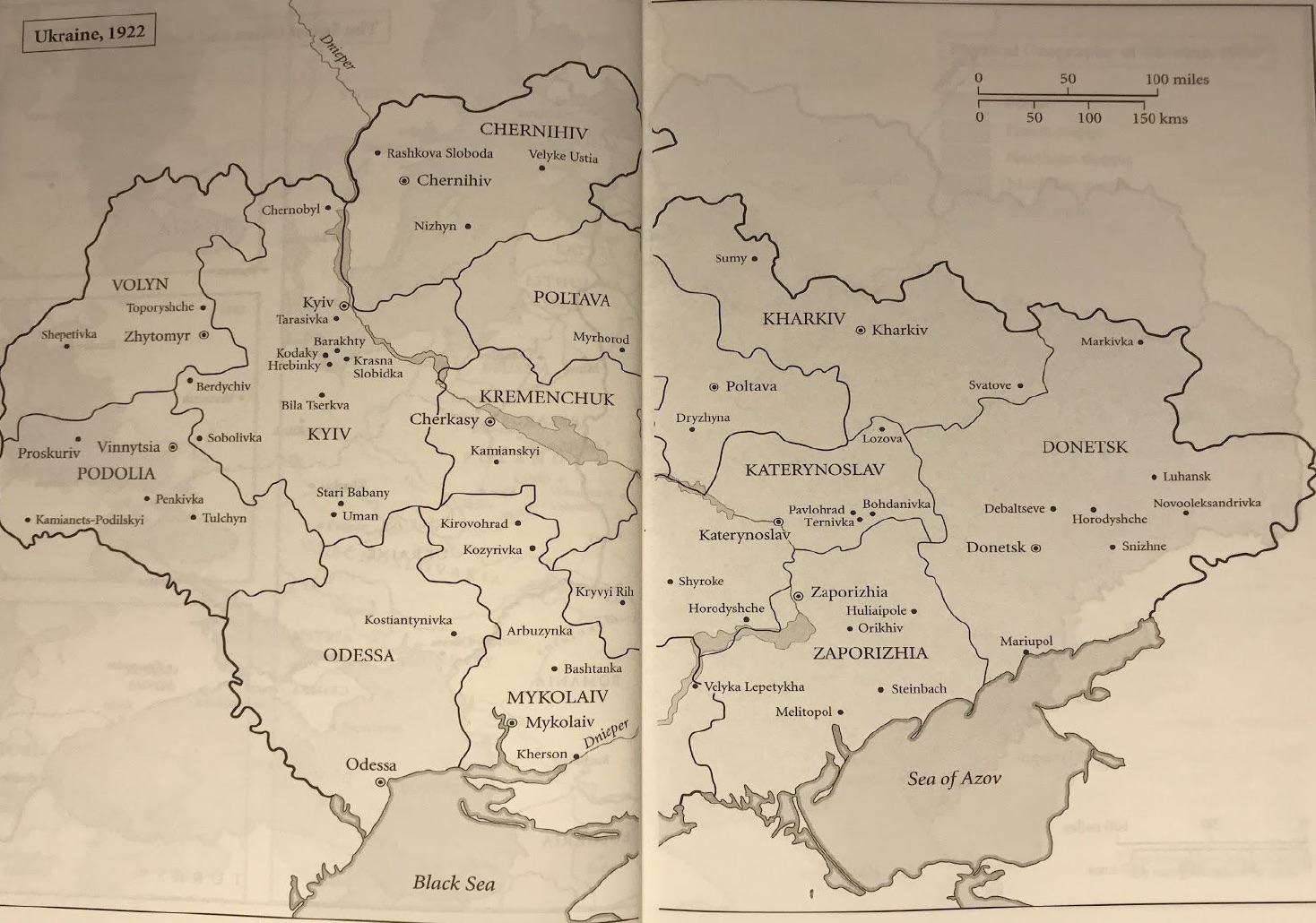

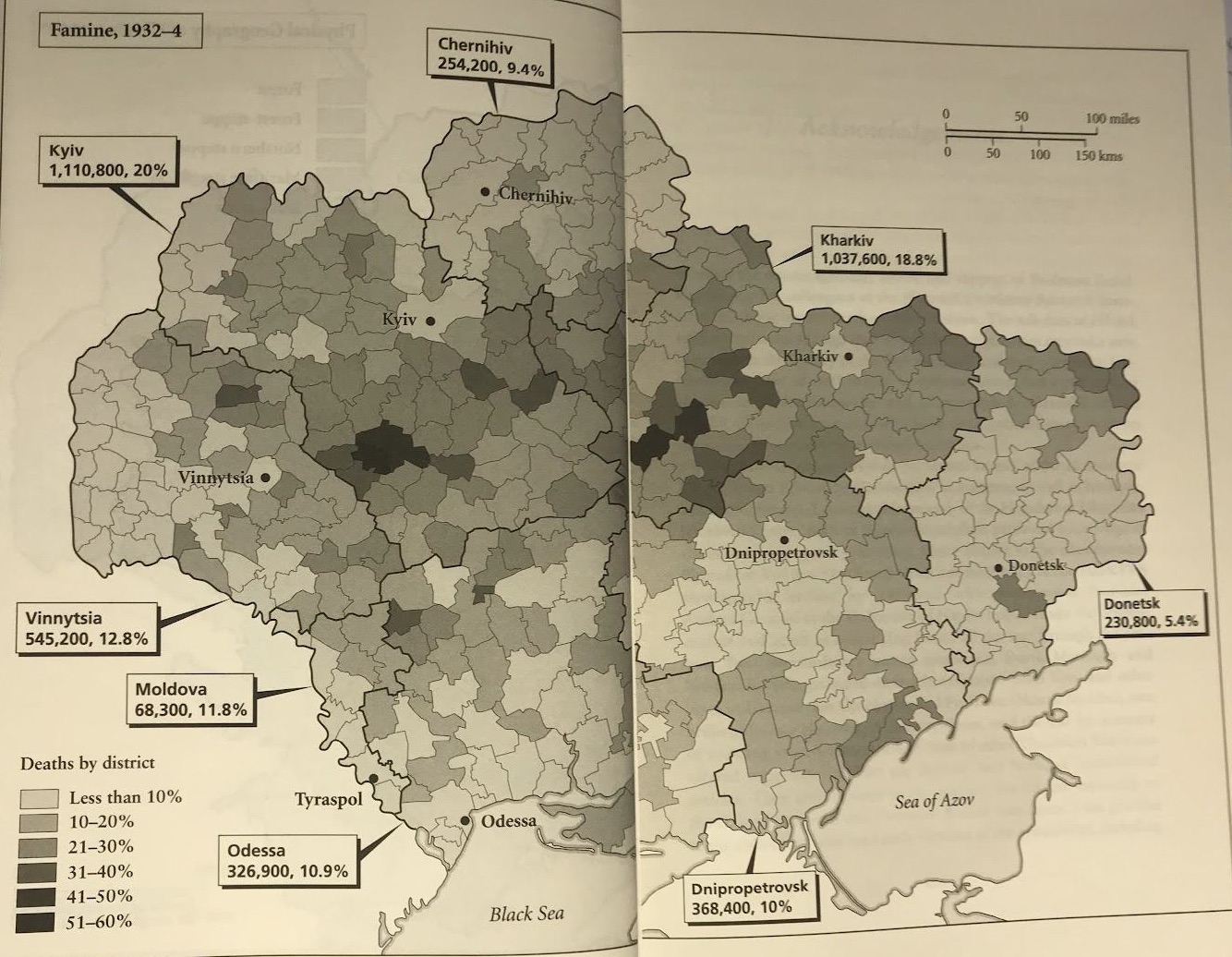

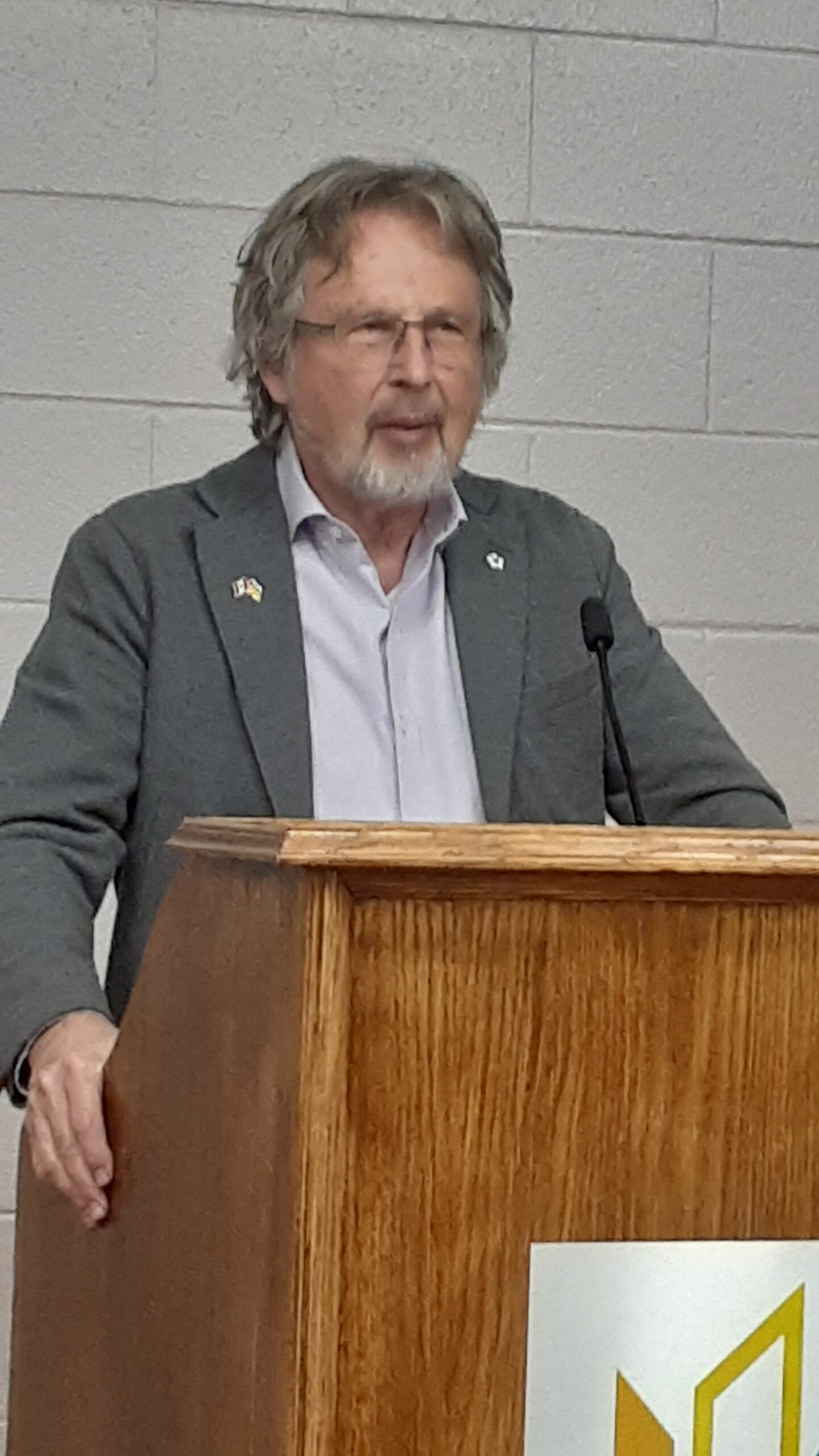

Image 1: This is an image showing the borders of the provinces of Ukraine in 1922, ten years before the Holodomor from Anne Applebaum’s compelling book, “Red Famine.”

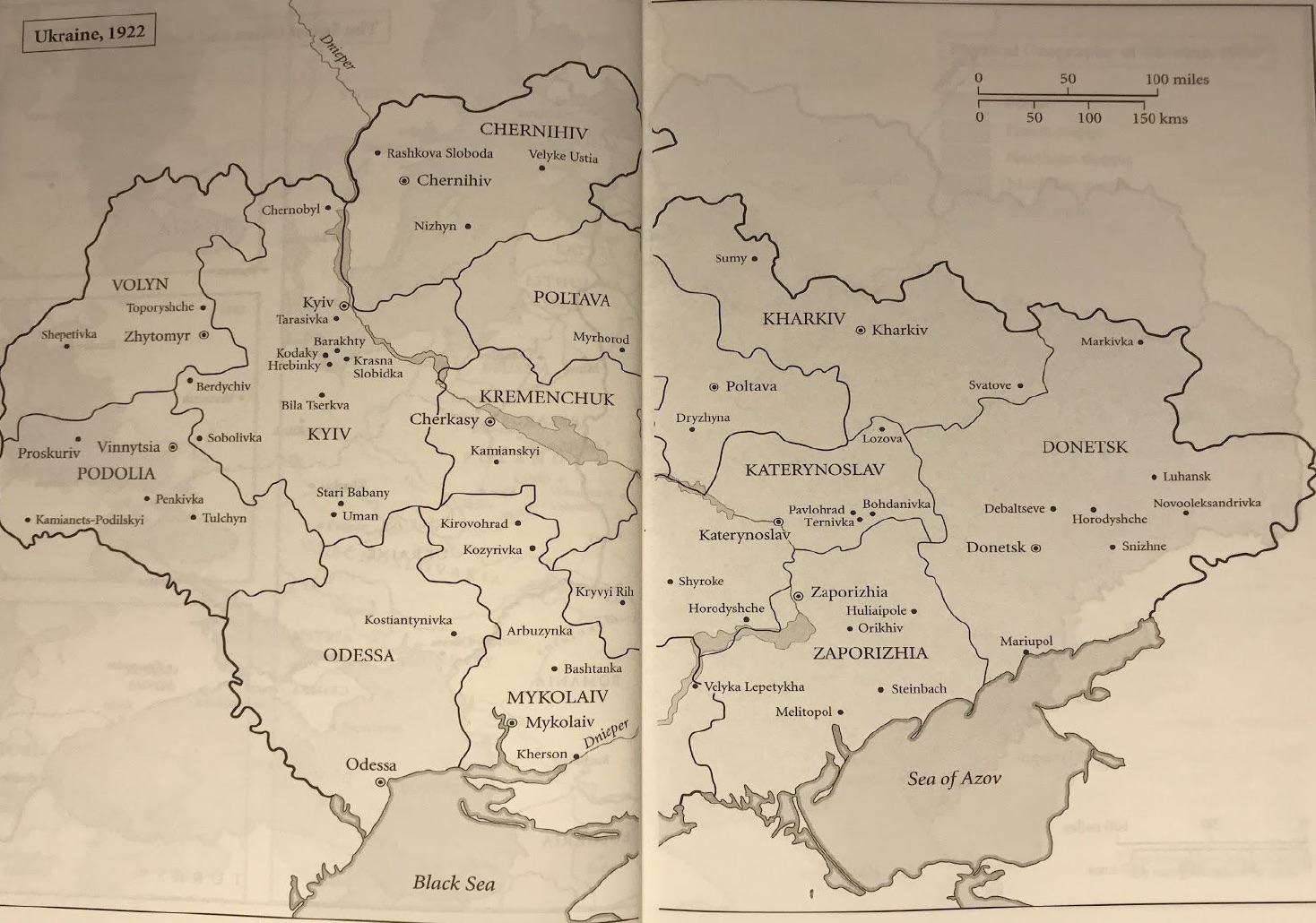

Image 2: This next photo, also from Anne Applebaum’s “Red Famine,” shows the count and percentages of deaths in different districts throughout Ukraine.

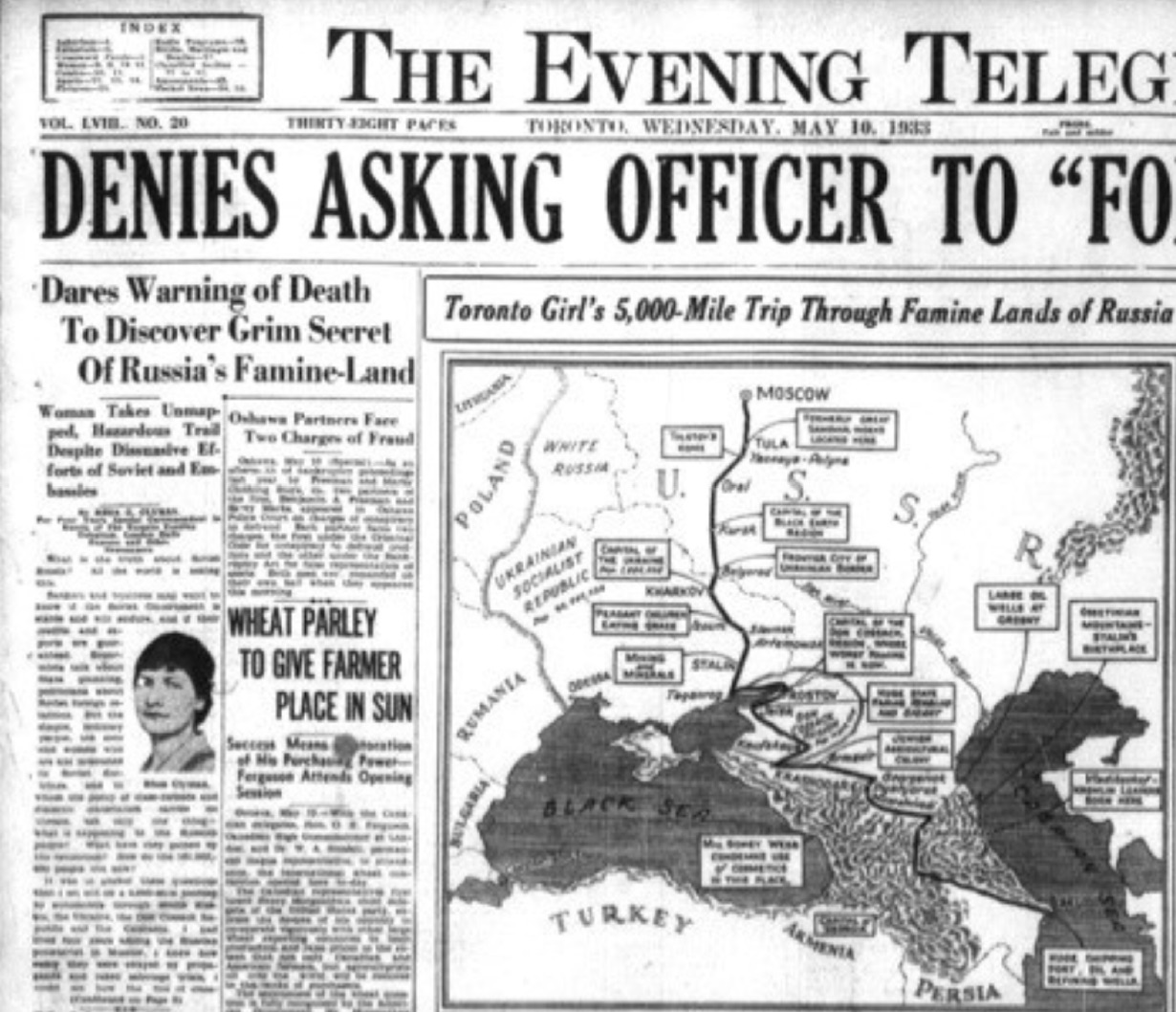

Rhea Clyman

An individual who was instrumental in facilitating the history of the famine via oral sources was Rhea Clyman. At the age of two, Clyman and her family immigrated to Canada for a better life and more opportunities. When Clyman was 24, she travelled to the Soviet Union in hopes of making life better for herself as a freelance foreign correspondent. Many journalists were sent to the Soviet Union, however only stayed for a short time. As Clyman knew the language and had already experienced life there, she had a unique perspective to propel into her writing. During her time in the USSR, Clyman went to Kem, a city in northern Russia, the location of many Soviet camps. In Kem, she met some of the wives of the prisoners and uncovered the Soviets' use of political prisoners as forced labourers.

Clyman became disillusioned with Stalin's plans, knowing the Russian language allowed her to move around freely, witnessing many traumatic events. While in Ukraine, there were many occasions where peasants came up to her revealing the severity of the famine.

When driving in the countryside in 1932, Clyman stopped in a village along the way, asking locals where she could purchase eggs and milk. The villagers did not understand her, one proceeded to leave and return to show her their frail fourteen-year-old child. He explained to her how the village was starving as there was no bread to eat and in desperation for food the children were eating grass. This experience unveiled to Clyman the widespread impact of the famine and inspired her to share the reality in the villages.

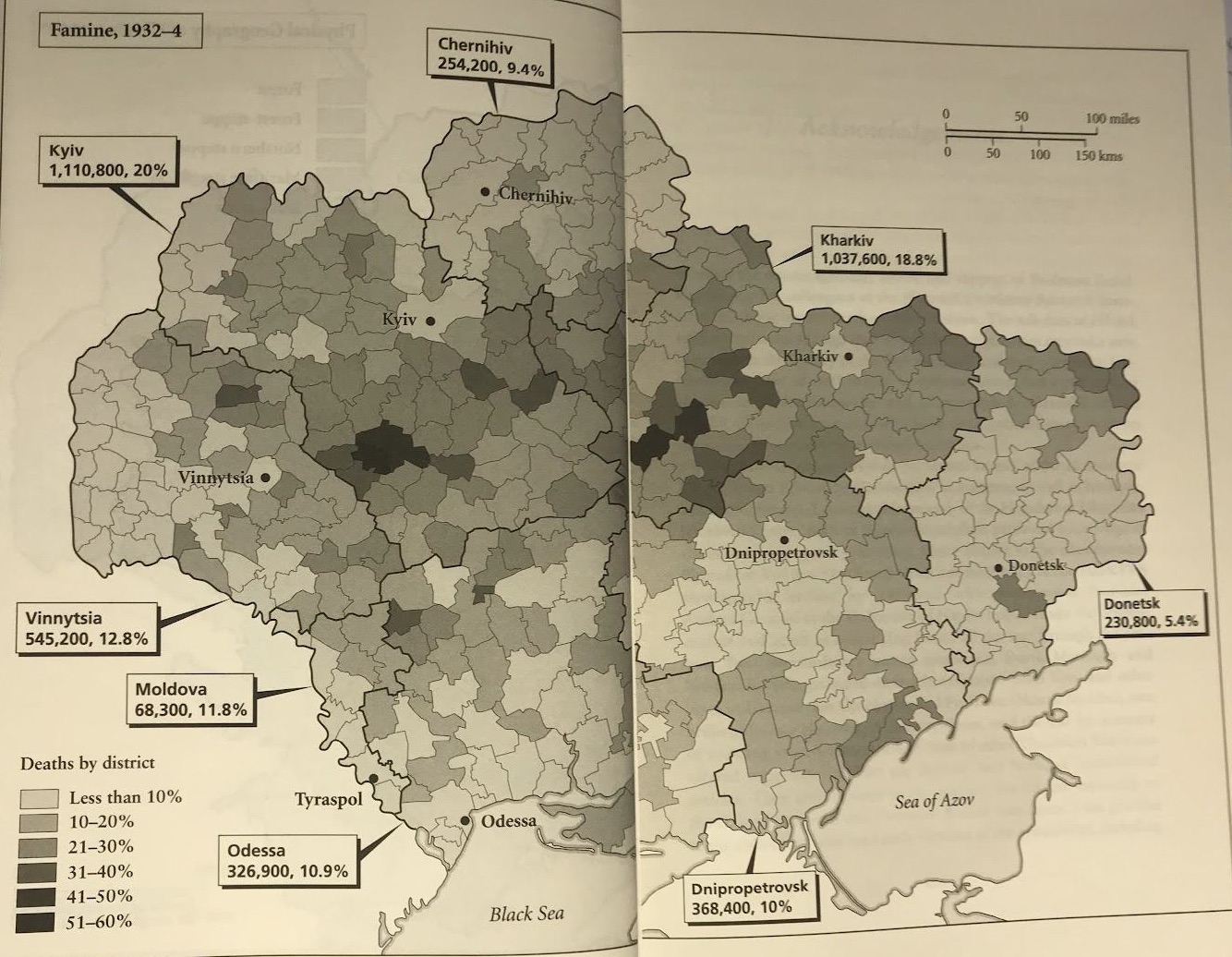

Clyman wrote about her experiences in the Toronto Telegram, the largest Canadian newspaper at that time. Professor Jaroslaw Balan, of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Alberta, first became interested in Clyman’s work when looking through Canadian news articles written about the famine. He notes:

“She went to the Soviet Union feeling very optimistic, [expecting that there would be] no unemployment, that men and women were equal, but she very quickly came to the realization that this was an incredible totalitarian state, how poor people were, and how difficult their lives were.” (Masis, Julie, et al., 2017)

Her work allowed the exposure of the famine and unspeakable ongoing suffering in Ukraine to the Canadian public and she took many risks in publishing this information and evidence. The risks she undertook in exposing the famine have opened the doors for people seeking the truth of what happened in Ukraine.

Rhea Clyman passed away in New York in July of 1981, at the age of 76. “Certainly the passion, courage, and keen eye for detail that she exhibited in her reports from the Soviet Union at a critical juncture in its evolution, certainly deserve to be better known not only by students in Soviet history, but by all of the descendants of those who suffered through the beginning years of Stalin’s quarter-century reign of terror.” (Masis, Julie, et al., 2017)

Discussing the Holodomor or sharing information about its existence was a crime in Ukraine until the 1980s. The only people who knew about it were those who lived through it, and yet they were afraid to speak of it for decades.

“Only with the closest and most trusted of friends would we talk about the terrible news from the villages… The rumors were confirmed when the townspeople were ordered to the countryside to help with the harvest and saw them-selves whence had come the living skeletons that haunted our city’s streets.” (Applebaum, 2017, pg.304)

This quote conveys the challenging experience for the Ukrainians and acts as concrete evidence against the denial of the famine. After classification of the the famine as a genocide, many more survivors came forward. “Privately, however, the survivors did remember. They made real or mental notes about what happened. Some kept diaries, ‘locked up in wooden boxes’ as one recalled, and hid them beneath floorboards or buried them in the ground. In their villages, within their families, people also told their children what had happened.” (Applebaum, 2017, pg.326) Applebaum illustrates the urgency Ukrainians had to ensure their stories were documented and preserved as testimony to the horrors they faced. “Elida Zolotoverkha, the daughter of the diarist Oleksandra Radchenko, also told her children, her grandchildren and then her great-grandchildren to read it, and to remember ‘the horror that Ukraine had passed through’.” (Applebaum, 2017, pg. 326)

A great deal of denial surrounded the Holodomor, which has misled many into thinking that it never happened. Andrew Gregorovich, who was a Senior researcher for the Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre in Toronto, addressed this denial in a speech he made about the genocide. He explained an experience with his professor where he prepared a presentation on exploring the truth behind several myths about the USSR, including the Holodomor. His professor continued to believe it did not happen. To prove him wrong, Andrew provided him with eyewitness accounts from the Black Deeds of the Kremlin translated by his father. Even when provided with proof of the famine, the professor dismissed it due to the fact that the research took a “Ukrainian viewpoint.” Despite individuals' recollections and proof, it is surprising that people continue to deny the catastrophic experiences and occurrences that took place, discounting the genocide and those who suffered. (Ukrainian Canadian Congress & Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre)

Images 3 & 4: Photos of front-page news articles from the Toronto Telegram written about Clyman’s experiences during the Holodomor. (Feduschak, Natalia A.)

Zina Mayewsky

Zina Mayewsky was a Holodomor survivor who lives in Toronto and was a long-standing member and principal at Lesia Ukrainka School in Etobicoke. In an interview, she explained her experience and her family’s efforts to survive. When the Russian government eliminated the elites, intellectuals and important figures and sent them to Siberia, Mayewsky’s uncle, a judge, was sent to Siberia for 10 years. Lack of leadership in Ukrainian villages and communities caused the people to act like “sheep without a shepherd.” (Mayewsky, Zina) During the night, Russian officers would visit Zina’s home, looking for her father and asking her mother to give up his passport, at this point her father was long gone. He escaped by going to Kyiv on foot, taking with him gold jewellery to pawn for bread or a small amount of money. He went into hiding for three months without communicating with the family. They survived eating only crushed cucumber seeds at meal times, which they had hidden and saved from their garden. In addition to the removal of all food sources, the communists implemented high property taxes forcing families out of their homes, claiming they were enemies to the Russian nation, the Mayewskys’ were one of them. Zina’s mother and her three children were alone with nowhere to go. Zina remembers holding onto her mother’s skirt crying, not knowing what would happen next, until fortunately they were offered a room with their very kind Jewish neighbour. They provided them with a small portion of food and one bed for all four of them to sleep on. As time passed, their father sent a letter saying to meet with him in town, the family were finally reunited. They fled to another town in Western Ukraine where the famine occurred and successfully hid from the authorities for 10 years.

For many years, Zina did not openly share or talk about her experiences. When she became a principal, she saw the importance of telling her story to her students every year on the day that marks the famine's remembrance in Canada, the fourth Saturday of November. Mayewsky shares with her students the life she had to live during this time, describing the horrors she witnessed throughout her childhood, emphasizing how many people the famine affected and killed. The most important point she stresses is that this event is to be remembered by all and to never happen again. She encourages the new generation to continue commemorating

Holodomor remembrance every year and to continue to campaign for its awareness.

Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin was considered the first scholar to analyze the Holodomor, having had superior knowledge of political aspects, international law and the Soviet legal system. For the 20th anniversary of the remembrance of the famine that took place in New York in 1953, Lemkin wrote a paper titled, The Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine. Lemkin first coined the term “genocide” which he then put forward to the United Nations (UN). After the examination of the devastating outcomes of the famine, it was clear that the event was “not simply a case of a mass murder,” but, “a case of genocide, of the destruction, not of individuals only but of a culture and a nation.” (Romanyshyn, Oleh, et al., 2014, pg.6)

Lemkin’s work in the United States and with the United Nations contributed to the significant uncovering of the Holodomor and brought awareness of the famine to many nations around the world.

Conclusion

Thanks to the anecdotes and awareness raised by those above and others, the Holodomor is now recognized as a genocide against the Ukrainian people worldwide. In the contemporary world, more international governments have accredited the famine and have taken action to recognize its impacts. Canada was one of the first countries to formally acknowledge the Holodomor in their federal government by creating a document entitled, Debate of the Senate. The four main aspects included were: recognizing the Holodomor, stopping any spread of false information, designating the fourth Saturday of every November to commemorate the victims of the genocide, implementing true historical facts into Canadian records, and incorporating them into the education systems. James Bezan, a member of parliament, and Raynell Andreychuk, a senator, were the driving forces of passing Bill C-459 on July 19, 2003. This increased an appreciation of the famine on a national level and encouraged other nations to follow suit. The United States of America, numerous European countries and the UN General Assembly began to recognize the Holodomor as a genocide.

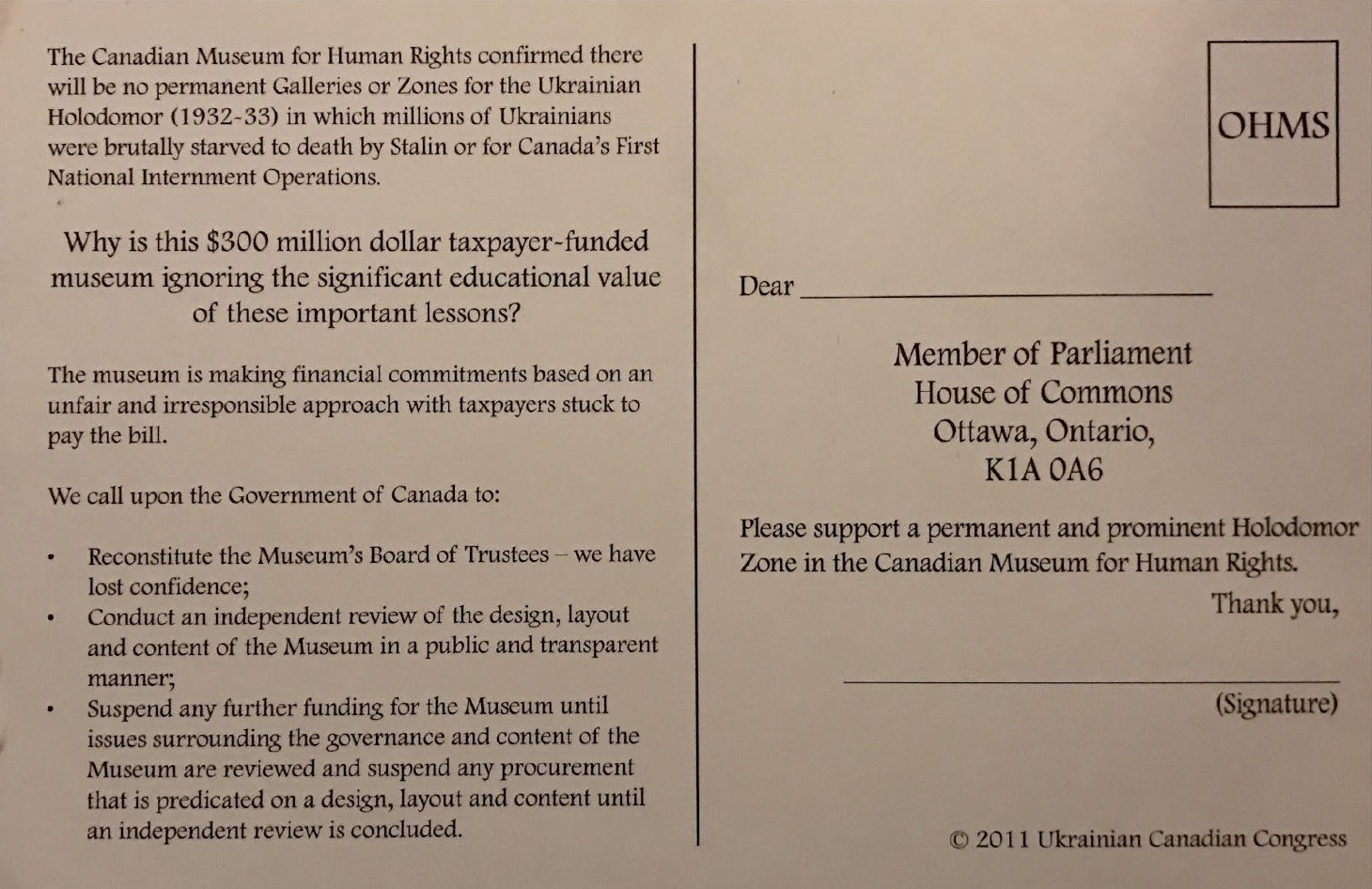

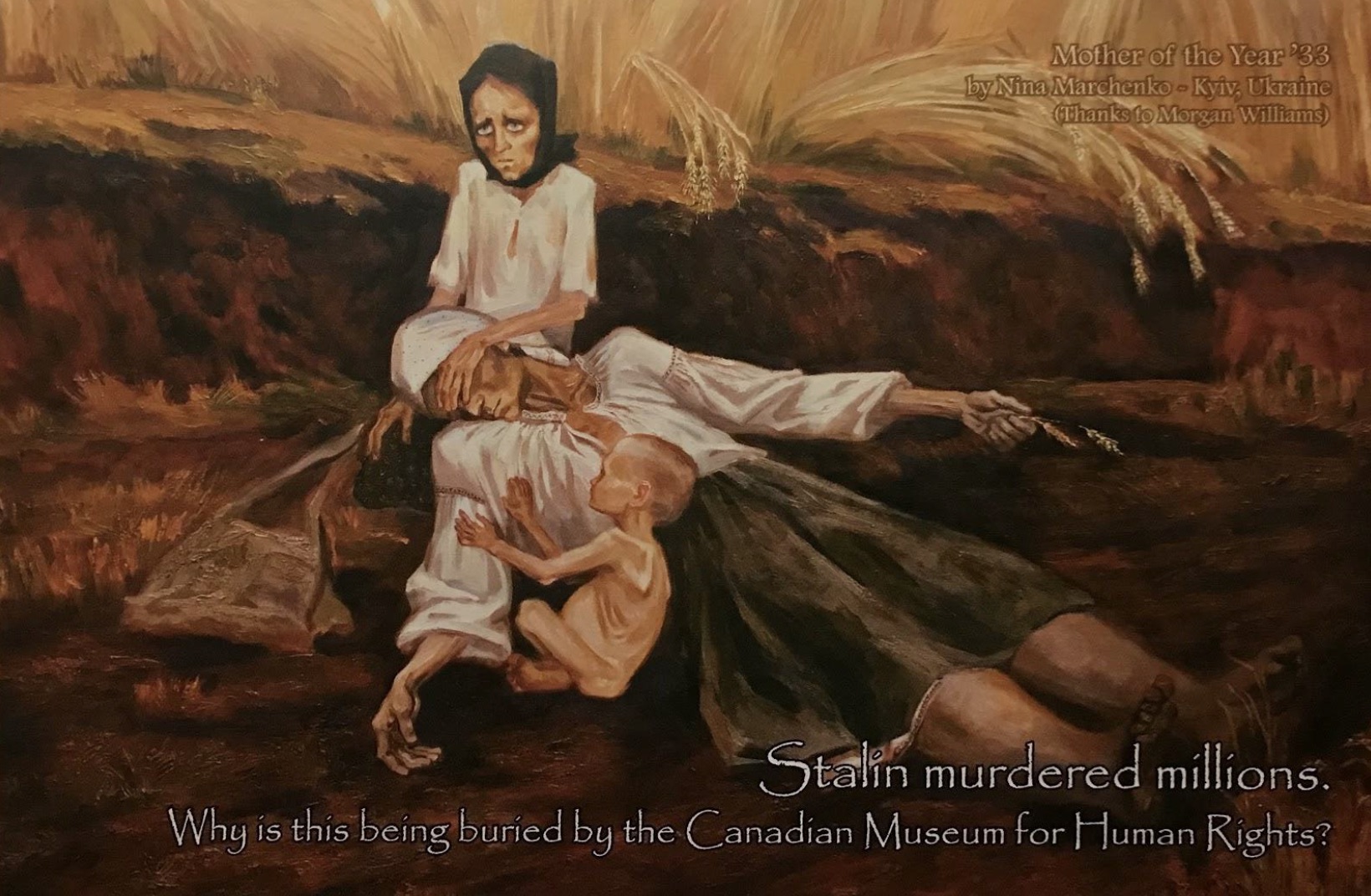

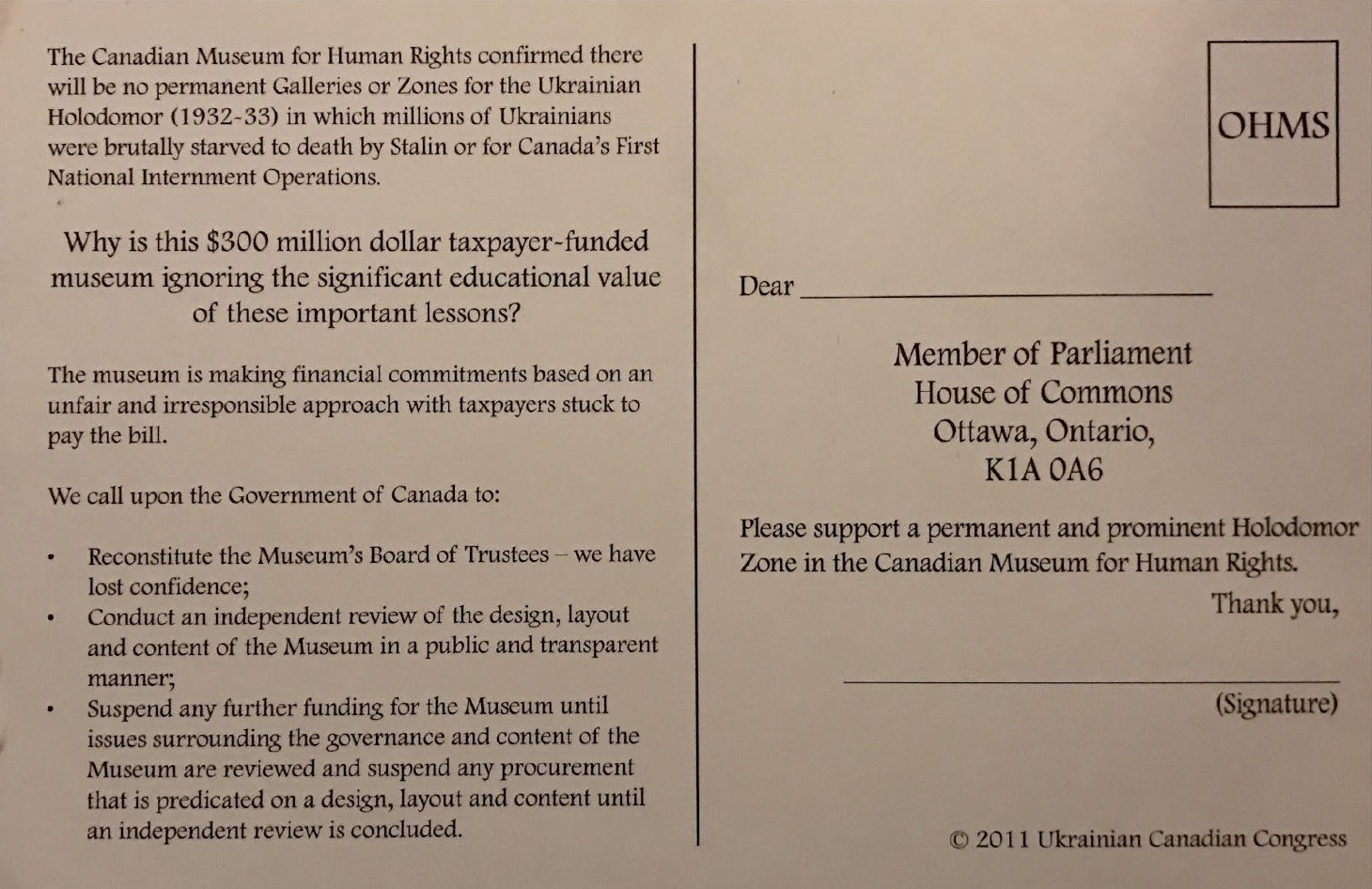

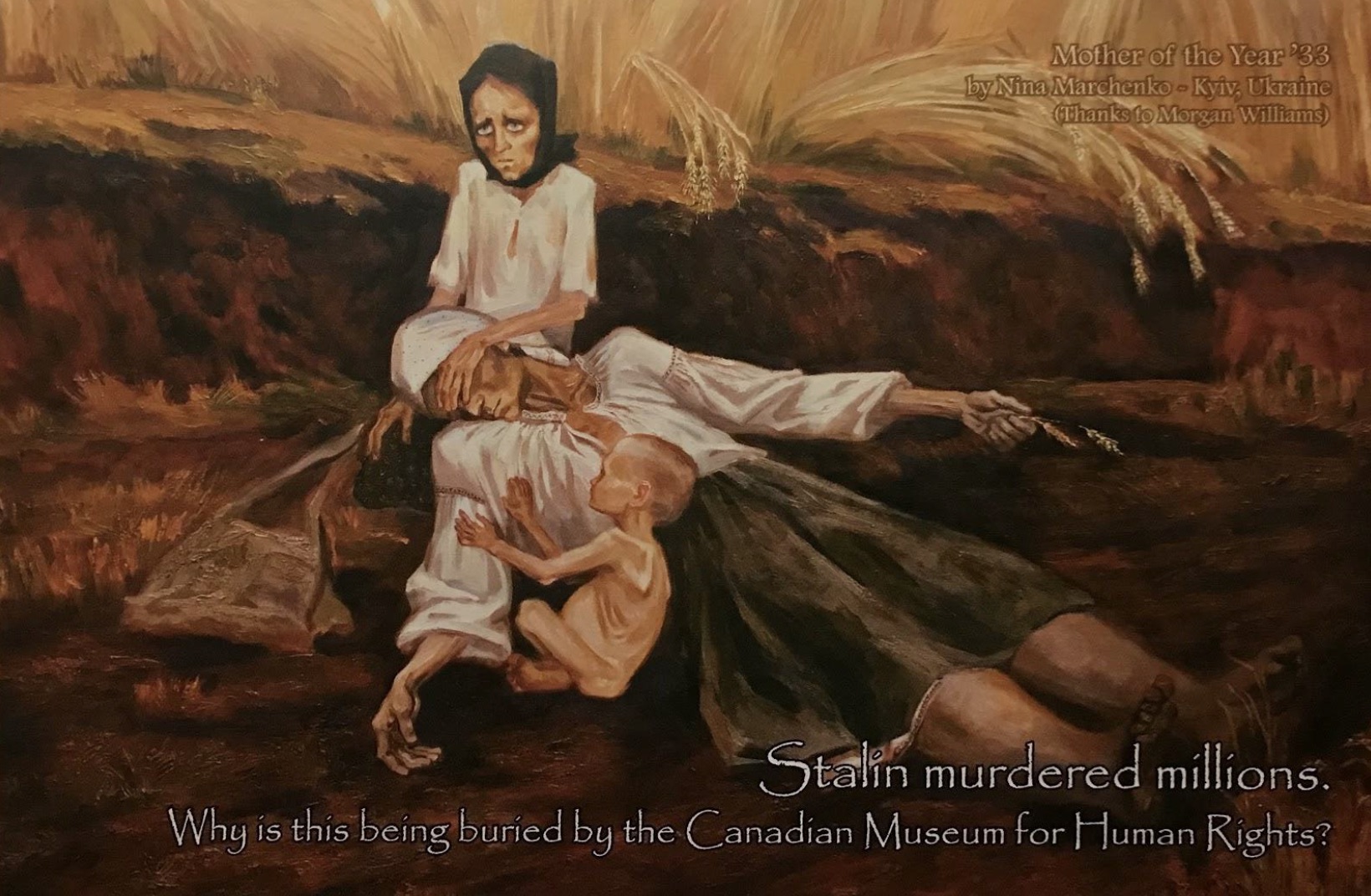

Image 5 & 6: The pictures above show postcards that were distributed at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights to people who wanted to participate by sending a prepaid postcard to a member of Parliament in the House of Commons. Some oral histories may also be paired with paintings and other visual representations of what it was like during the famine.

Oral history has been vital in preserving the events of the Holodomor. The communication of life experiences and documentation of accounts have been vital in creating archives for future generations to seek information about the past and to learn from the wrongs of history. The oral histories that have been passed on directly from the victims themselves, such as Zina Mayewsky, are key in illustrating the atrocities faced by Ukrainians and the importance of preserving the voices of the victims. These personal accounts connect the reader to the victim, aiding them to understand the reality of life in those times. Our moral duty is to ensure that personal stories such as Zina’s are preserved for the people of tomorrow.

Over ninety years have passed since the heinous famine occurred. In remembrance, we should honour, preserve, and pay tribute to the innocent lives who perished at the hands of Stalin. The extermination of Ukrainians and the great efforts of concealing the famine have been unravelled by the courage and strength of survivors. The continued support of the academic community and recognition of the famine worldwide has attributed to the continued success in the preservation of evidence, ensuring the rejection of false denials and the protection of victim accounts.

“Bread could have saved us then… Remembrance will save us now!” (Romanyshyn, Oleh, et al., 2014)

Bibliography

- Naimark, Norman M. Stalin's Genocides. Princeton Univ. Press, 2012.

- Perloff, James. “Holodomor: the secret holocaust: when Ukraine resisted Soviet attempts at collectivization in the 1920s and '30s, the Soviets used labor camps, executions, and starvations, and starvation to kill millions of Ukrainians.” The New American, 16 Feb. 2009, p. 31. Academic OneFile.

- Klid, Bohdan, and Alexander J. Motyl. The Holodomor Reader: a Sourcebook on the Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 2012.

- “Zhinka z Ukraïny opovidaie pro holod i liudoïdstvo” (A Woman from Ukraine Tells of Famine and Cannibalism), Ukraïns'kyi holos (Ukrainian Voice, Winnipeg), 13 September 1933. Excerpts, pp. 1, 5. Translated by Alexander J. Motyl.

- Mckenna, Yvonne. “Sisterhood? Exploring Power Relations in the Collection of Oral History.” Vol. 31, no. 1, 2003, pp. 65–72.

- Masis, Julie, et al. “How a Female Jewish Journalist Alerted the World to Ukraine’s Silent Starvation.” The Times of Israel, 18 June 2017. Feduschak, Natalia A. “New Chapters in the Ukrainian-Jewish Relationship Explored at Canada's Limmud FSU (Part 1) – Rhea Clyman.” UJE – Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, 18 Aug. 2017.

- Balan, Jars. “Rhea Clyman: A Forgotten Canadian Eyewitness To The Hunger of 1932.” Ярс Балан. Репортажі Ріа Клайман з Подорожі По Східній Україні і Кубані Наприкінці Літа 1932 р. – Україна Модерна, Україна Модерна, 21 Nov. 2014.

- “Joseph Stalin.” Encyclopedia of World Biography, Gale, 1998. Biography in Context. Accessed 2 Sept. 2017.

- Romanyshyn, Oleh, et al. Holodomor: the Ukrainian Genocide 1932-1933. League of Ukrainian Canadians, 2014.

- Applebaum, Anne. Red Famine. Penguin Random House UK, 2017.

- Mayewsky, Zina. Personal Interview, 9 Sept. 2017.

- Ukrainian Canadian Congress & Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre, and Lesia Korobaylo. Famine-Genocide in Soviet Ukraine 1933. Edited by Lesya Jones, Ukrainian Canadian Congress & Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre, 1999.

- Holodomor The Ukrainian Genocide 1932-1933 published by the League of Ukrainian Canadians and Ucrainica Research Institute, Nov. 2014.