New antiquarian discovery at the SVI Library in Toronto

Thomas M. Prymak, University of Toronto.

A few days ago, I was on one of my frequent visits to the St Volodymyr Institute (SVI) Library in Toronto. I wished to do some work on Ukrainian history and was cheerfully greeted by the new librarian, Anastasia Baczynskyj. For the previous week or two, she had been busy straightening out the unshelved books and trying to put some order into the numerous donations that the library had recently received. This was no easy task. But she was enthusiastic about it and her enthusiasm was catchy.

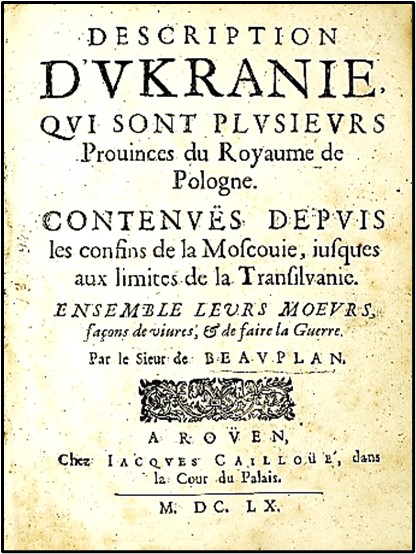

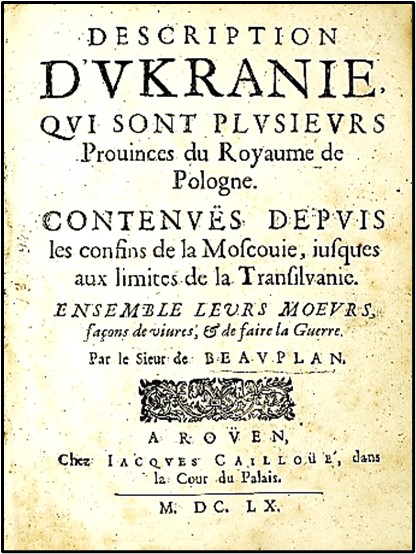

That day, however, was exceptional. She immediately ran up to me and exclaimed, “You will not believe what I have just discovered!” In a pile of old books and unordered papers and documents in a little-observed corner of a back storage room, and at the very bottom of this pile of books and papers, she had come across a carefully boxed and complete, undamaged, original French-language copy of the famous book of Guillaume de Beauplan, the Description de Vkranie (Description of Ukraine) published in Rouen in France in 1660!

Picture credit: Wikipedia

The book was adequately bound in a white leather cover and all the pages seemed to be there, quite readable, and clear. The book was printed on the beautifully durable paper of the seventeenth century, which is immediately recognizable to anyone who has handled very old books. Such books were made from old, washed and bleached cloth, and never wood pulp, which is much more acidic and decays more rapidly. Books printed on paper made from wood pulp only became common much later.

None of the pages of this little volume were in any way stained or severely damaged, and the paper was still quite white with no sign of deterioration, though they were, of course, quite brittle after some three and a half centuries and more on unidentified library shelves.

The book was accompanied by a note dated September 1985, mentioning a certain Mr Eugene Kurdydyk who had apparently donated it to the library. This Eugene Kurdydyk was almost certainly a son of the journalist and author, Anatol Kurdydyk (b. 1905), who is listed in Mykhailo Marunchak’s biographical dictionary of Ukrainian Canadians and has an entry on him in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

Anatol Kurdydyk was a poet, writer, and the editor of several Ukrainian Canadian newspapers, all with a conservative philosophical bent, including Ukrainskyi robitnyk (Toronto), Vilne slovo (Toronto), and Novyi Shliakh (Winnipeg). His son, Toronto resident Eugene, was an avid collector of books, maps, and other artifacts of antiquarian interest, all of them related in some way to Ukraine. About the same time when Eugene passed on these materials to the SVI, that institution also hosted an exhibit of antiquarian maps from his collection, which I attended. Many of these, so far as I remember, were beautiful examples of seventeenth and eighteenth cartography, most of them in full colour. Toronto residents, Christine and Walter Kudryk bought several maps from Kurdydyk and they are preserved to the present day in the very large Walter Kudryk Collection, which is in process of being transferred to Oseredok, the Ukrainian Cultural and Education Centre in Winnipeg.

Eugene’s documentation included a letter, this one to him from a contact who had approached an important antiquarian book expert in France; the latter testified to him in a letter written in French he had long been searching for an example of Beauplan’s book, complete with its original map included in a pocket attached to the back cover, but all three that he found in his career, even that of the famed Russian art critic Sergei Diaghelev, a founder of the modernist World of Art group, were missing this map.

But the new SVI copy had this map attached in such a pocket at the back of the book! Anastasia immediately recognized the importance of this book and its map, for not only was it now the oldest known book in the SVI Library, but it was also of extreme importance in Ukrainian history, particularly for old Cossack Ukraine. Beauplan was a contemporary of Cossack Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and the Frenchman was one of the first western Europeans to know Ukraine well and to use the name “Ukraine” in the titles of his books and maps; for he had been an engineer and cartographer in the employ of the King of Poland Wladislaw IV, and Ukraine was for many years ruled by the Poles, afterwards partially expelled by Khmelnytsky’s Cossacks in the Great Wars of 1648-57.

In fact, “Beauplan,” a surname in French meaning something like “beautiful map,” was probably accorded him, or taken on by him, for his pioneering work on Ukrainian cartography or engineering. (He had also designed several royal fortresses across Ukraine.) His full name, so far as we know, was “Guillaume le Vasseur Sieur de Beauplan.” “Le Vasseur” was probably his original surname; but that was in a century when surnames were still quite malleable for persons of non-noble background. “Vasseur” in French means “vassal” originally a rank somewhat below that of a baron.

The full title page of Beauplan’s book in English translation reads “A Description of Ukraine, Containing several Provinces of the Kingdom of Poland, Lying between the Confines of Muscovy, and the Borders of Transylvania, Together with their Customs, Manner of Life, and How they Manage their Wars, by the Sieur de Beauplan.” So, his definition of Ukraine was quite expansive, extending far beyond the borders of today’s Ukrainian national state. On another level, the name of its most important inhabitants of that time, “the Cossacks,” is missing from this title page but is probably what is meant by the “they” (leurs/their) in this title. Inside, however, Beauplan gives much new information about these Cossacks.

Beauplan mostly reported what he himself saw and this included how the Cossacks elected their leaders, how they made war, their relations with the Tatars, how the Tatars took captives from among the common people, and the cruel fate of such people in Tatar captivity. Beauplan also described the customs, manners, and morals of the Cossack people. These included a vivid description of Cossack marriage customs.

All this information was copied and disseminated across Europe for the next two hundred years and more. Henceforth, many maps were printed with the title “Ukraine, Land of the Cossacks,” and somewhat later, “Ukraine, Land of the Old Cossacks.”

According to Beauplan specialist A. B. Pernal of Brandon University in Manitoba, in the 1600s, the book itself was translated into Latin, Dutch, Spanish, and English, and in following years was reprinted many times. A particularly important English edition was printed in London in 1744, and a notable French edition was published in Paris in 1861. (I have originals of both in my private library, acquired from the private collection of the late Andrew Gregorovich of Toronto.)

A Russian translation edited by the historian F. Ustrailov came out St Petersburg in 1832, and it had a great influence upon the Ukrainian National Awakening that was just then in its initial phase. (The poet Taras Shevchenko’s first Kobzar (The Blind Minstrel), or book of poems, came out in 1840.) But the newly discovered SVI Library copy is the original “expanded edition of 1660.” The first (1651) had been much shorter, and of it, only 100 copies were printed.

But the expanded edition now rediscovered in the SVI is more detailed and of much greater historical value. Moreover, on the antique book market, this little book would probably fetch many thousands of dollars. A quick search of Bookfinder.com revealed that none are available today.

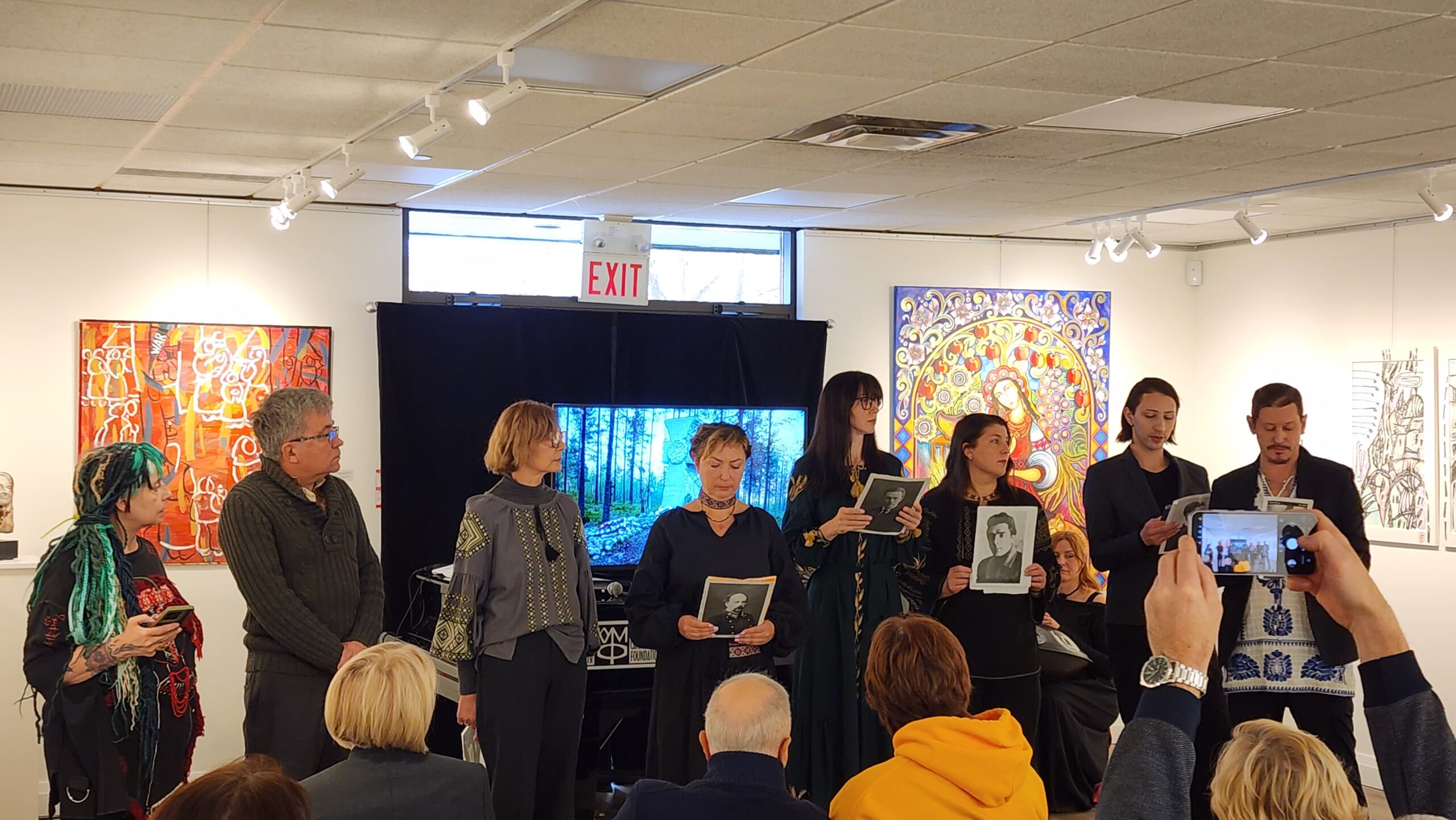

Ms Baczynskyj and the SVI Library are to be congratulated for this important find, which is so very significant for understanding where Ukraine fit onto the map of Europe in the 1600s, what transpired there just before and during Beauplan’s lifetime, and how the country fits into European history today.

THOMAS M. PRYMAK, PhD, is a Senior Research Fellow at the Chair of Ukrainian Studies, Departments of History and Political Science, University of Toronto. He is the author of several books and numerous articles and reviews on Ukrainian and Ukrainian Canadian political and cultural history, art history, and philology, including etymology and onomastics (name studies).

Share on Social Media